It happened in January, inside California’s Santa Clara County jails. In April of last year, it happened at the Westville Correctional Facility in Indiana. It happened two separate times this year alone at the St. Louis City Justice Center. American prisoners erupted, many often refusing to go back to their cells until they were heard. As one man who had spent months confined to the notorious facility in Missouri told a journalist, rebellion is “their only grievance system.”

What motivated these protests was a disastrous COVID-19 response that has left prisons and jails utterly ravaged. There has been no way for those on the inside to isolate from, nor to care for, those who are sick from the virus, and their mortality rate is significantly higher than that of the general population. In federal and state prisons, according to the UCLA Law COVID Behind Bars Data Project, there have been 199.6 deaths per 100,000 people, compared with 80.9 in the total U.S. population. “They are someone’s family,” the mother of a young man incarcerated in the Indiana prison told a local reporter. They are simply asking, she said, “to have open and honest communication about where the virus is and what is being done.”

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

That the pandemic remains dire behind bars, or that it has fueled protests there, may raise few eyebrows. But the uncomfortable truth is that there have been hundreds of moments of unrest just like these in recent years, dramatic episodes in which America’s incarcerated people have risked extraordinary punishment just to let the public know how bad conditions really are.

The attention people serving time do manage to attract may be laced with surprise, or skepticism. It isn’t that Americans can’t imagine prisons as hellholes; after all, many have seen movies like The Shawshank Redemption. But it is as if the disproportionately Black and brown people serving time have surrendered not only their freedom but also any claim on sympathy. Those on the outside are quite confident that the incarcerated today are legally protected from the cruel and unusual tortures of the past and, given that, many are remarkably comfortable with the idea that prisons are pretty terrible places of punishment—comfortable forgetting that how a society doles out such discipline is a reflection of its moral capacity.

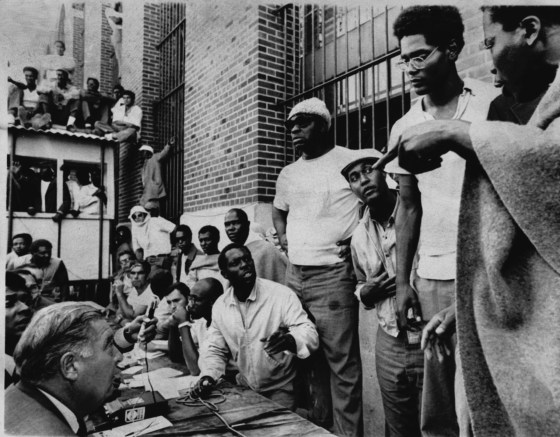

It is true that extraordinary effort was put into improving conditions inside America’s prisons and jails back in the 1960s and ’70s. Exactly 50 years ago, from Sept. 9 to Sept. 13, 1971, the nation watched riveted as nearly 1,300 men stood together in America’s most dramatic prison uprising, for better conditions at the Attica Correctional Facility in upstate New York. The men were fed on 63¢ a day; were given only one roll of toilet paper a month; endured beatings, racial epithets, and barbaric medical treatment; and suffered the trauma of being thrown into a cell and kept there for days, naked, as punishment. The Attica prison uprising was historic because these men spoke directly to the public, and by doing so, they powerfully underscored to the nation that serving time did not make someone less of a human being.

Now, despite the protections won by their rebellion, and the broader movement for justice of which it was a part, the incarcerated are once again desperately trying to call the public’s attention to the horrific conditions they endure behind the walls. The 50th anniversary of the Attica prison uprising is an occasion that compels making sense of why that is. These are institutions that we fund as taxpayers and send people to as jurors, and those inside of them are not exaggerating how bad the conditions really are. But how could they have deteriorated so markedly over the past five decades, and why have so many cared so little as it was happening?

The answer to these questions can be found by taking a closer look at what happened at Attica and in its aftermath. Even as key demands were won in the prisoner-rights movement that peaked that long-ago September, the horrific way that state officials chose to end the bold and hopeful protest would have an incalculable impact on criminal justice nationwide for decades to come.

We are firm in our resolve, and we demand, as human beings, the dignity and justice that is due to us by our right of birth. We do not know how the present system of brutality and dehumanization and injustice has been allowed to be perpetrated in this day of enlightenment, but we are the living proof of its existence, and we cannot allow it to continue …

—Attica Manifesto

When the incarcerated today come together demanding better medical care in the face of COVID-19, they are hoping that laws already passed will be followed and constitutional rights already acknowledged will be honored. The men at Attica believed they also had these rights, but few had yet been secured in either law or policy.

Of the 33 demands that the men at Attica would present to state officials during their four-day uprising, the right to be protected from the cruel and unusual punishment of having their most basic medical needs ignored was one of the most central. For decades, every man at Attica had lived in terror of getting sick. Attica’s doctors were notorious. One physician’s response to a prisoner’s agonized plea for pain medication for a broken hand was infamous: “Write a letter to a different doctor.” As the prisoners expressed it most pointedly in the Attica Manifesto, a document they had sent prison officials two months before the uprising: “The Attica Prison hospital is totally inadequate, understaffed, and prejudiced in the treatment of inmates … There are numerous ‘mistakes’ made many times, improper and erroneous medication is given by untrained personnel.”

Attica’s men succeeded in getting New York’s Commissioner of Corrections Russell Oswald to agree in negotiations to “provide adequate medical care,” as well as to “access to outside doctors and dentists,” and then, in the wake of their rebellion, both houses of the New York State legislature were willing to consider reforms to prison medical care statewide in 1972. Then, in 1976, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down its landmark ruling Estelle v. Gamble, which established clearly that “deliberate indifference by prison personnel to a prisoner’s serious illness or injury constitutes cruel and unusual punishment.”

Read more: Inside the Attica Uprising: A Doctor in D Yard

Yet in 2021, and not just as a result of COVID-19, the incarcerated across the country still somehow find themselves much sicker than they need to be, dying unnecessarily painful as well as early deaths. According to journalist Keri Blakinger’s investigation for the Marshall Project, correctional systems often hire people to provide care who have few if any qualifications, or even licenses that have been restricted or suspended. And because they can’t afford the usurious co-pays many prison systems now require, many prisoners who are ill can’t even see the doctor to begin with.

Much of prison health care is now privatized, aimed at profits. This means not just billing practices totally unsuited to a prison population, but also the denial of lifesaving procedures. That medical abuses related to privatization are a regular occurrence behind bars is corroborated by the physicians themselves, according to the ACLU. As one Arizona doctor who was expected to provide care for more than 5,000 people revealed, not only were her requests for consults with a specialist always denied, because “it costs too much money,” but she also regularly ran out of prisoners’ medications.

It is this sort of nightmarish medical care that cost John Kleutsch his life last summer in a Washington State prison. Kleutsch was recovering from outpatient abdominal surgery when a nurse asked to transfer him to a hospital, but the prison’s medical director refused. After “multiple days of abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, no exams, no written notes and no plan of care,” the Seattle Times reported, Kleutsch was finally transferred to the ER, where he died of acute pancreatitis, gastrointestinal perforation and septic shock.

Abysmal medical care wasn’t the only reason Attica’s prisoners stood together. They also regularly experienced abuse at the hands of guards who had total control over them, and this too became a top issue they hoped officials would remedy 50 years ago. And the prisoners made an important mark on history. Their uprising was a real wake-up call to corrections professionals across the country who, thereafter, began insisting on many more hours of guard training. In New York State, specifically, the Department of Corrections began to hold training sessions devoted to “attitudes in supervision,” as well as “prejudice” and “minority cultures.”

Today, however, in states like New Mexico, it would be hard to convince those trying to serve their sentences that they have a right to decent medical care or to be protected from abusive guards. Not only is a crippling and easily treatable bone disease called osteomyelitis now at “epidemic levels” there, but according to legal documents, when those suffering this painful condition complain that they are being denied the care they need, they risk severe retaliation and solitary confinement from officers.

Even though prison officials vigorously resist outside calls for greater transparency, information that gets out indicates clearly that what prisoners endure in New Mexico is not exceptional. In 2012, for example, despite repeated denials from the Department of Corrections that anything untoward had happened to him, it was revealed that in Florida a prisoner named Darren Rainey had been forced into a prison shower by correctional officers and left for two full hours under a spray that registered 180°F, with the doors locked, until his skin began peeling off. Rainey died. None of these officers was held responsible.

In New Jersey’s only institution for women, 31 corrections officers and supervisors were recently suspended for abuses. One woman there was beaten so badly while she was handcuffed that she is now confined to a wheelchair, yet she and others like her spent years too fearful to come forward. As they told the Department of Justice, to dare to report anything is to live under the constant “threat of retaliation” from the same guards who assaulted them in the first place.

Those most vulnerable to guard abuse are the minors behind bars, who now total some 52,000 children. Juvenile facilities are not required to tell parents about what’s happening to their kids, but because of tenacious journalists we know that in 2021 a little boy in a facility in Maine can have his face smashed into a metal bed frame by a prison employee, have his teeth knocked out and then have that same guard refuse him medical care. When the public learned that staff members at a youth facility in Michigan recently restrained a child so viciously that they rendered him unconscious, it was only because that child died.

One of the very cruelest punishments that officers regularly mete out to children in prisons today is to lock them in isolation. When guards threw 15-year-old Ian Manuel into a solitary cell in 1992, it was, according to his memoir, for infractions as insignificant as “having a magazine that had another prisoner’s name on the mailing label.” He found refuge in his own mind, writing it was “the only place I could play basketball with my brother or video games with my friends and eat my mother’s warm cherry pie on the porch. It was the only place I could simply be a kid.”

In 1971, Attica’s men were acutely aware of the importance of stopping this form of punishment. Their demand that prison officials stop placing human beings in segregation—in solitary confinement—had been articulated in writing well before they were pushed to protest. But no matter how hard these men pushed during the September uprising, this was one of the demands on which they simply could not get Commissioner Oswald to budge. He would not agree to end solitary, nor would he consider their position that anyone sentenced to isolation must at least have due process.

Since 1971, the capricious and excessive use of solitary confinement has only intensified in America’s prisons. Over the past decade, the limited data that outsiders have been able to get out of correctional institutions revealed that between 60,000 and 90,000 Americans were in a solitary confinement cell—but the actual number was likely higher. Whether in segregation for “administrative,” “disciplinary” or “protective” reasons, to be in complete isolation for 22 to 24 hours a day, for days, months and years on end is unequivocally understood to be a form of torture, by the U.N., Amnesty International and numerous medical bodies.

In some places, isolation is used simply as a means of dealing with overcrowding. In Tennessee, for example, county administrators send people awaiting trial to the state prison because local jails are too crowded, under that state’s so-called safekeeping law. Even though these people have not even been convicted of a crime, they are then held in solitary until their trial dates.

As one man, William Blake, wrote of his 25 years in solitary confinement in the state of New York, “If I try to imagine what kind of death, even a slow one, would be worse than 25 years in the box—and I have tried to imagine it—I can come up with nothing.”

Countless infractions could land a man at Attica in solitary, but one of the quickest was to refuse to work. The labor they were forced into could be grueling, it paid mere pennies per hour, it had no meaningful health or safety protections, and Black and brown prisoners’ jobs were far worse and lower paid than those of white prisoners.

Fury over the injustice of this led Attica’s men to launch a sit-down strike for better wages in July 1970, and the issue stayed with them. And, although they were unable to secure an end to segregation, they did get New York’s Commissioner Oswald in fact to agree to “recommend the application of the New York State minimum-wage law standards to all work done by inmates.”

Despite these protections, thanks to the Constitution’s 13th Amendment, unpaid prison labor is still legal today. In fact, in 2021, every barrier to the use of prison labor that had been in place in 1971 has been eliminated, and there are more than a million more people behind bars available to work for little to no money than there were back then. This has not gone unnoticed. Be it for a private company seeking cheaper labor costs or a governor looking to break collective bargaining agreements, prison labor has became increasingly attractive over time.

In Wisconsin, former governor Scott Walker brought in prisoners to do landscaping, painting and snow-shoveling jobs that used to be done by unionized workers. In small towns like Iola, Kans., incarcerated women are working for the Russell Stovers candy factory. The Florida Times-Union reports that prisoners in the state labor in unbearable heat, “running weed-eaters and busting up sidewalks,” without sufficient breaks or food. Corrections officers are the foremen, and they motivate with threats of discipline. Working on the road crew earns the incarcerated no money. These same people must still pay for most essentials in prison, and many have children on the outside whom they must still feed. Prison labor also means fewer paid jobs for those on the outside. Over a five-year period, the income not going to either the families of unpaid prisoners or the folks who would have been doing those jobs if free labor weren’t available totaled “around $147.5 million,” the report continued. Add in “actual wages and benefits,” and the sum is “likely double or triple that estimate.”

It turns out that it is no accident that the full possibilities of the Attica moment were not realized, that Americans are largely unaware of what the costs of it have been for the people inside our nation’s prisons, and that this nation grew so hard-hearted when it came to how people in prison were being treated over the past five decades. This was the outcome intended by state officials 50 years ago.

As those nearly 1,300 men at Attica invited reporters to show the public what prisons really were like, as they brought in observers to oversee negotiations with prison officials, and as they gave passionate speeches about the conditions they had so long endured, Americans across the country found themselves deeply moved. Few liked the fact that these men had taken hostages to ensure that state officials would bargain with them, but they appreciated that Attica’s men released those who had needed medical care and took care to protect the rest.

As the days wore on, as more media from around the country descended on the prison, optimism ran high. Crucially, these men’s struggle was not taking place in a vacuum. It resonated with other efforts to expand civil and human rights, from Montgomery to Cicero and Selma to Stockton. And by the night of Sept. 12, to widespread astonishment, Attica’s men and Commissioner Oswald had managed to come to an agreement on 28 of the 33 demands. A peaceful end was in sight. Lives depended upon Governor Nelson Rockefeller’s making it work.

During the long days and nights that they had been negotiating, outside the prison waited more than 600 New York state troopers, itching to retake Attica with guns blazing. And they would get their wish. On the fifth morning, against the advice of every one of the observers as well as the pleas of his own state employees being held hostage, and with the men inside just waking up, Rockefeller ordered the armed retaking of Attica.

Within 15 minutes, 128 men were shot and 39 lay dead or dying—prisoners and hostages alike. As one traumatized National Guardsman put it, the troopers’ assault left in its wake “more blood, more gunshot wounds and more injuries that day than most people see in a typical day in combat. Certainly, in Vietnam.”

And then, stunningly, state officials stepped outside the prison and blamed this carnage on Attica’s prisoners themselves. The ostensibly peaceful protest was really about murdering guards in cold blood, the officials told the assembled press. The prisoners had slit the throats of corrections officers, officials said, and one guard had even been castrated.

This lie went out in headlines and on front pages from the New York Times to the Los Angeles Times to small-town papers across America. Those who had been rooting for the men in Attica found themselves recoiling in horror. People began questioning not just prisoner rights, but the broader prisoner reform and civil rights movements. When word began circulating of troopers and guards mercilessly torturing the naked and wounded prisoners within minutes of gaining control of the facility, the information was impossible to corroborate.

Read more: How Attica’s Ugly Past Is Still Protected

The way state officials would then cover up what had happened at Attica, and their decision to prosecute 62 prisoners for “riot-related” offenses, would, over time, do incalculable damage to the substantial national public sympathy for prisoners’ rights. Of course, the movement was not crushed immediately. Because broader support for delivering on America’s promises of equality still existed, a great many of the things the men had fought for at Attica would be implemented. This explains how the incarcerated could still get victories like the Estelle v. Gamble ruling.

Ultimately, however, for the American public writ large, pummeled not just by mistruths about Attica but also about protester “violence” across the country in this period, there was no coming back. When Governor Rockefeller chose to end the Attica uprising the way he did, he wanted to show the nation he was as tough on crime as the rest of the Republican Party. To do so, he had to lie that these prisoners hadn’t really wanted better conditions, that they were just violent thugs.

The price of believing him was high. The anti-prisoner fire that state officials lit on the last day of Attica would, over the next five decades, engulf the nation, even as the prison population jumped by almost 800%—numbers unlike any seen in U.S. history.

Today, even many of the most tough-on-crime voters have come to recognize that handling so many social and economic problems via the criminal-justice system has cost this nation dearly. And with that recognition has come the very real possibility of criminal-justice reform. But for at least a decade now, attention has been devoted almost solely to the drivers and consequences of this explosion in America’s prison population, not to the places where mass incarceration is experienced firsthand. And even though the criminal-justice reform movement has managed to move mountains on critically important issues ranging from sentencing reform to drug laws, when it comes to reducing the number of people still in prison in this nation, the needle has barely moved.

But just as 1971 was a moment of possibility, so might 2021 be one as well. When the men at Attica stood up for their rights, it was at a time when others on the outside were doing the same. The moment was ripe for change. And so it is again. Americans today, from jails in St. Louis and prisons in Indiana, to cities such as Chicago and Minneapolis, have begun imagining, indeed demanding, a more just and equal future. In states like New York, thanks to this sort of vision, combined with effort from both the inside and outside, long-term solitary confinement will finally be abolished.

If this nation hopes, this time, to achieve a justice system that is, in fact, just, it must remain ever vigilant for any echo of the lies told at Attica. Had Americans really seen these men’s fates, their lives, their opinions, their expertise and their place in the nation as truly equal to their own, that massacre, the torture, those lies and the criminal-justice crisis that we now live with simply could not have happened. They would not have allowed it.

But that would have been a different world—one in which Americans back then understood that people serving time were what they remain today: our brothers, our mothers, our children. They are us.

Thompson, a professor at the University of Michigan, is the Pulitzer Prize–winning author of Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy.