In the aftermath of the attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, rumors of sabotage and imminent further attacks found fertile ground in the minds of a nervous American public. In a press conference shortly after inspecting the damage, Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox attributed (without evidence) their precision in hitting military targets to a “fifth column” in Hawaii who had aided the enemy. Speculation and panic proliferated—fishermen aiding the Japanese navy, farmers poisoning vegetables, and strikes on power lines and other critical infrastructure.

Amid this frenzied atmosphere, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt appealed for calm. She traveled to California just days after the attack, and made a point to meet and be photographed there with Japanese Americans—a decision that angered many.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

Read more: 3 Myths About Pearl Harbor, According to a Military Historian

Eleanor, who decried “foolish prejudices about other races,” once again implored readers of her newspaper and magazine columns that those of Japanese ancestry “must not feel that they have suddenly ceased to be Americans,” and that such a crisis was the time for “really believing in the Bill of Rights and making it a reality for all loyal American citizens, regardless of race.”

Those rights were in a precarious place within her husband’s administration. The government almost immediately froze many Japanese Americans’ assets, but she convinced the Treasury Department to allow withdrawals for critical living expenses. And when she returned to Washington, she conferred with numerous officials, attempting to counter the momentum for sweeping action against Japanese Americans.

But other prominent voices continued to echo the drumbeat of suspicion. In February of 1942, influential writer Walter Lippman amplified Knox’s warnings of a “fifth column” comprised of immigrants and their descendants, and criticized Washington for hesitating to impose “mass internment” of these “enemy aliens.” Fellow columnist Westbrook Pegler likened him to a contemporary Paul Revere, and declared “to hell with habeas corpus until the danger is over.”

This rhetoric mirrored internal pressures on President Franklin D. Roosevelt. General John DeWitt, who led the Western Defense Command, wrote on February 14, 1942 that the “Japanese race is an enemy race” who, regardless of birthplace, would be ready to die for Japan. He dismissed the lack of evidence of any such plots as an elaborate ruse designed to create a false sense of security. Earl Warren, then California’s attorney general, agreed that Japanese Americans were “ideally situated… to carry into execution a tremendous program of sabotage on a mass scale.”

Such racially-charged language tapped into long-standing resentment and prejudices. Despite comprising a small percentage of the population, Japanese Americans “were despised as economic competitors,” says Greg Robinson, professor of history at l’Université du Québec À Montréal and author of By Order of the President. For decades, Japanese immigrants had faced a host of laws barring them from land ownership, citizenship, and further immigration—antecedents of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 that targeted immigrant laborers.

“I think the incarceration of Japanese Americans really was an outcome of the Yellow Peril stereotype that was fomented by politicians and institutionalized in other policies directed against Asians in the U.S.,” adds Russell Jeung, professor of Asian American Studies at San Francisco State University.

Read more: The U.S. Put Norman Mineta in an Incarceration Camp. Then He Went to Congress

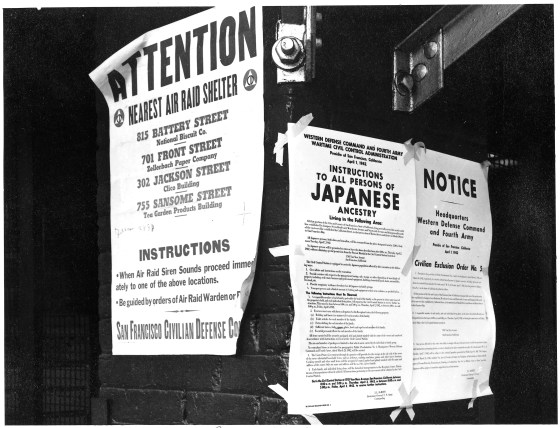

This entrenched legal disenfranchisement made it easier to target “aliens” on pre-existing surveillance lists who were promptly arrested without charge. For Japanese Americans, Roosevelt’s Depression-era warning that fear itself was to be feared was becoming a painful reality. And on Feb. 19, 1942, he signed Executive Order 9066, paving the way for the forcible relocation of an estimated 120,000 people (which, according to a national poll, a majority of Americans agreed this was needed). Overnight, lives were torn asunder as “evacuees” were hastily gathered at “assembly centers” and taken to “relocation centers”— euphemisms for the camps that imprisoned them through much of the war.

Once the Order was in effect, Eleanor faced a quandary as the nation’s wartime first lady. “Unlike [her husband], she does not believe that wartime emergencies override civil liberties protections,” says Allida Black, editor emeritus of the Eleanor Roosevelt Papers Project and a distinguished visitor scholar at the University of Virginia Miller Center for Public Affairs. So what she could not contradict, she mitigated. She offered her support in myriad ways, corresponding with Japanese Americans, donating from her own funds, meeting with civic groups, helping to establish scholarships—and later, meeting with wounded Japanese American soldiers.

Her most visible engagement was her visit to the Gila River internment camp in Arizona in the spring of 1943. She refuted assertions residents were being “coddled” and praised their improvements to the austere desert surroundings. In an unpublished draft of an article she wrote for Collier’s magazine, she wrote that “to undo a mistake is always harder than not to create one originally but we seldom have the foresight.”

In media interviews, she was more measured, acknowledging the official line of military necessity but supporting conditional release, saying that the “sooner we get the Japanese out of relocation camps the better.” These public comments indicated that she was conflicted, but pragmatic. “She’s not actively challenging the policy,” says Robinson. “She’s trying to make things better for people within the policy.”

“She had no doubt that internment was unconstitutional,” says Black. Yet, for the remainder of her life, she refrained from criticizing her husband’s decision or mentioning her own advocacy.

Read more: I’m Tired of Trying to Educate White People About Anti-Asian Racism

In 1943, restrictions were gradually eased for many Japanese in the camps, albeit based in part on the premise of a flawed questionnaire intended to determine their loyalty. Two of those questions caused deep rifts within incarcerated communities; one asked about the willingness of military-age men to be drafted, and the other asked them to swear allegiance to the United States—and forswear imperial allegiances they had never held. Many Nisei (second-generation) men jumped at the chance to enlist, but others objected to what they saw as the unfair premise of the questions, given their imprisonment and the inability of first-generation arrivals to gain citizenship. It proved to be a double-edged sword: The divergence enabled the creation of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, whose story is one of uncommon bravery and sacrifice. Yet it also sent those branded as disloyal to harsher conditions at the Tule Lake camp in California.

Eleanor’s words about the challenges of undoing a mistake were prescient. Despite the loyalty questionnaire, military victories in the Pacific, and the fact that War Department officials had not seen the concerns about military necessity for internment borne out, it wasn’t until late in 1944—after much bureaucratic deliberation—that Executive Order 9066 was lifted.

A report by a congressionally-established commission later confirmed that “not a single documented act of espionage, sabotage or fifth column activity was committed” by those Order 9066 targeted. It concluded that “race prejudice, war hysteria and a failure of political leadership” resulted in a “grave injustice” against them.

“We know that in periods of war, periods of pandemic, periods of economic downturn, racism increases against Asian Americans,” Jeung says. Last year hate crimes against Asians rose by 339 percent, according to a report by the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism. A November 2021 survey by Stop AAPI Hate, which Jeung co-founded, found that 1 in 5 Asian Americans reported hate incidents since the start of the pandemic.

Eleanor’s defense of Japanese Americans in that prevailing climate of hostility created added risks for her, too. “Eleanor is the most beloved and most hated first lady up until that time,” says Black, pointing to her refusal of Secret Service protection—instead choosing to carry her own pistol—despite consistent death threats against her.

But fear has many facets—constructive and destructive—that emerge under duress. Asked by a reader what she feared most, the First Lady responded that it was to be “afraid—afraid physically or mentally or morally—and allow myself to be influenced by fear instead of by my honest convictions.”