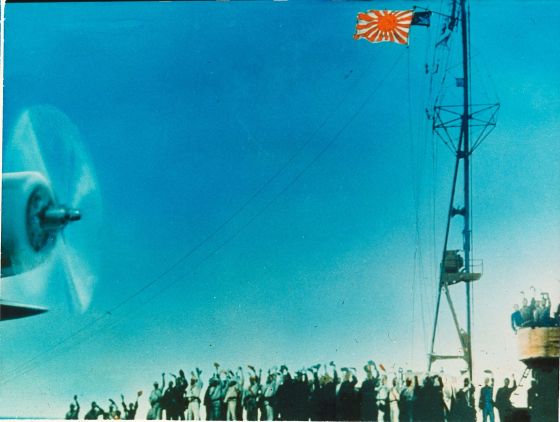

Within half an hour of the bombs falling on Hawaii, the phone rang in President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s study. When the navy secretary came on the line, his voice was quavering: “Mr. President, it looks as if the Japanese have bombed Pearl Harbor.” At first, all Roosevelt could say was “No.”

He then turned to his principal adviser, Harry Hopkins, and told him the message from Honolulu: “We are being attacked. This is no drill.”

Hopkins was incredulous. His first thought was that, “there must be some mistake and that surely Japan would not attack in Honolulu.” His expectation, in line with all the principal military officials and civilian leaders in Washington, was that any Japanese attack would begin with a British or Dutch colony—certainly not a core American territory on the other side of the Pacific. Yet Roosevelt recalled that Japan had initiated war with Russia in 1904 in a similar way by striking its naval base at Port Arthur. this was “just the kind of unexpected thing the Japanese would do,” he remarked, “and that at the very time they were discussing peace in the Pacific they were plotting to overthrow it.”

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

The full report of the destruction took time to reach Washington. At 2:28 p.m., the chief of naval operations, Admiral Harold Stark, telephoned the White House to confirm the earlier reports, he could only state that “it was a very severe attack and that some damage had already been done to the fleet and that there was some loss of life.”

At 2:30 p.m., the president authorized Stark to implement War Plan 46—effectively empowering the U.S. fleet to conduct unrestricted submarine and naval war in East Asia and the surrounding waters. He reminded Hopkins of “his earnest desire to complete his administration without war,” but said that if the news from Hawaii was accurate then, “it would take the matter entirely out of his own hands, because the Japanese had made the decision for him.”

Roosevelt had indeed earnestly tried to keep the United States out of war in the Pacific, but this was less true with regard to the Atlantic. If Japan had in fact struck Hawaii and unambiguously brought the Americans into war, the unanswered question was: What did this mean for America’s relations with Germany?

Besides notifying his cabinet principals, Roosevelt personally telephoned the ambassadors of the major Allied powers to inform them of the attack. The British ambassador confided to his diary that Japan had made “the biggest mistake in their history” by uniting Americans against them, and it would be “interesting to see whether Germany now follows suit.” For the British ambassador to the U.S., Lord Halifax, who had scorned by American non-interventionists since his arrival as he worked to bring the U.S. into the war on Britain’s side, this was a moment to savor. When Lady Halifax learned the news, she asked their butler to open a bottle of champagne, claiming that there had been a birth in the family.

The toast was premature, and not only because the destruction in the Pacific was far worse than initially thought. The British mission in Washington would now have to reckon with how the new war would impact American supplies to Britain.

Earlier that day, even before Pearl Harbor, Halifax had communicated to London that American shipping assistance was increasingly threatened by the transfer of “Lend-Lease” aid to other countries, particularly the Soviet Union, as well as America’s own “preparation for possible Far East War” and the “consequences of that war if peace efforts fail.” A “rising tide of anti-British feeling” in Congress, stoked by the America First Committee, made this situation even worse. Britain’s diplomats, already fearful that the country’s “unpopular” image would undermine the American “urge to assist us,” cautiously waited to see how developments in the Pacific would affect their attempts to acquire desperately needed supplies.

Read more: Inside the 80-Year Quest to Name Pearl Harbor’s Unknown Victims

Soviet officials shared these fears. When news of the Pearl Harbor attack arrived in Moscow, Stalin’s relief that the Japanese had not attacked him was offset by anxiety about this diversion of British and American resources. Territorial losses, enemy action, and disruption caused by the evacuation program of Soviet citizens fleeing a German military invasion had slashed his own production, and he could not spare further support. As Stafford Cripps, the astute British ambassador in Moscow, had already noted, there was a recognition on the Soviet side that “although the Germans will be very much weakened” by the Soviet counterattack, “they will still have a tremendous power of production to build up a mechanized force again during the winter and next spring.”

Just before 9 p.m. at Chequers, Winston Churchill’s butler Frank Sawyers brought in a small radio so that the prime minister could hear the evening news. But as the newsreader summarized the headlines, Churchill remained “immersed in his thoughts” and completely missed the special dispatch.

A startled Averell Harriman, Roosevelt’s envoy to Europe and coordinator of the “Lend-Lease” program, burst out from across the table, “What’s that about bombing Pearl Harbor?” The target seemed so implausible that Churchill’s aide-de-camp Tommy Thompson thought the presenter had actually said “Pearl River,” a major waterway in southern China.

Recalling that he’d promised to follow any Japanese attack on the U.S. with a British declaration within the hour, Churchill announced, “We shall declare war on Japan” and headed for the door. U.S. ambassador John Winant and Harriman talked him out of this, cautioning that he could not declare war on the basis of a radio announcement, “even from the BBC.” Winant encouraged Churchill to first call the White House and find out the facts.

Churchill would later write in his history of the Second World War that, in bringing America into the conflict directly, the Pearl Harbor attack delivered him “the greatest joy.”

“So we had won after all,” he wrote. “England would live; Britain would live; the Commonwealth of Nations and the Empire would live.” “Hitler’s fate,” Churchill continued, “was sealed. Mussolini’s fate was sealed.” “As for the Japanese,” he wrote, “they would be ground to powder.”

But Britain was by no means out of the woods either. Churchill’s instinctive relief reflected the fact that Britain had avoided the worst-case scenario: fighting Japan and Germany across two oceans without American aid. But if the U.S. and Britain were “in the same boat” in the Pacific, then what about the Atlantic? After Churchill replaced the receiver and his initial excitement subsided, a new fear loomed: that the U.S. would focus entirely on Japan, devoting its resources to its own war and leaving Britain to face Hitler unaided.

Read more: I Survived World War II. Nationalism Is a Path to War

It was probably around this time that after-dinner discussions at Hitler’s bunker were dramatically interrupted. Hearing the news of Pearl Harbor on Reuters East Asian radio, press chief Otto Dietrich immediately raced to inform the Führer. Exercised by bad news from Russia, Hitler received him coldly. But when Dietrich cut him short by reading out the message, he reacted with astonishment. His face brightened and he asked tensely, “Is the news true?”

Hitler rushed to the Oberkommando de Wehrmacht (OKW) bunker to pass on the news in person. He burst in excitedly, the only time OKW head Wilhelm Keitel remembered him doing so during the entire war. All accounts of his reaction agree that the Führer was surprised—he clearly had no foreknowledge of the attack—and ecstatic. “I had the impression,” Keitel recalled, “that he felt as if freed from a heavy load.”

Throughout the coming hours and days, Hitler would express relief that Japan’s actions would tie down substantial British and American resources in the Far East. In any case, he was convinced that he was effectively already at war with America. And this time, unlike in 1917, the Reich would not wait to be openly attacked by the United States. Hitler would strike first.

There was no way, however, that the British, the Americans, or even the Japanese could be sure that he would actually do so.

Read more: The Real Biggest Myths About World War II, According to a Military Historian

In Washington, leading officials hurried to put the attack in its broader strategic context. When U.S. Secretary of State Cordell Hull returned to the State Department after a conference at the White House, he immediately convened his principal advisers. He was keen to stress his belief that the Japanese would not act unilaterally, and that the U.S. should expect Germany and Italy to join them. Consequently, he told his subordinates that “every American merchant vessel in the world should be notified of the existence of hostilities as it was feared that these vessels anywhere would be prey for German, Italian or Japanese armed forces.”

But sensitive as the president was to the threat from Germany, he also remained attuned to the attack’s likely impact on American public opinion—and the strength of anti-interventionist sentiment in Congress, aware that many of its members had denounced the administration’s policies in Asia and dismissed arguments against greater American involvement in Europe.

In light of sentiments like these, Roosevelt advised Churchill to avoid a British declaration of war until he had time to prepare American opinion himself. Although the hour was growing late, Churchill’s mind was racing, combing through the potential allies he would need as the war’s next chapter commenced. Before retiring for the night, he sent a dramatic message to the British representative in Dublin, which appeared to offer Irish unity in return for that nation’s support for the war against Hitler. At around the same time, he dispatched a telegram to the Chinese nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek to tell him that Japan had attacked both Britain and the U.S.: “Always we have been friends: now we face a common enemy.”

In Washington it was still early evening. The Roosevelt administration had still not received a declaration of war from official Japanese government channels. But in the White House, the telephone rang repeatedly with reports from the Pacific that grew ever more devastating. The death toll continued to climb; it was increasingly clear that damage to the U.S. fleet was enormous and many planes had been destroyed on the ground. before 6 p.m., Gov. Joseph Poindexter telephoned from Honolulu. In the middle of the call, hearing planes and anti-aircraft fire in the background, the president’s outer calm cracked and he exclaimed: “My God, there’s another wave of [Japanese] planes over Hawaii right this minute!”

(Tragically, what Roosevelt heard was actually America’s own gunners mistakenly shooting at a few remaining US planes, which were returning from an earlier pursuit of the Japanese raiders and fleet.)

As the evening was drawing to a close on the other side of the Atlantic, German naval leadership was also taking stock of a momentous day. “It remains to be seen,” its diarist wrote, “what immediate impact these events will have.” What was beyond doubt, he ventured, was that few states would be able to escape being caught up in a war that now embraced all the “great powers of the world.” Dec. 7, 1941, in short, “marked not only a new phase in the military operations” but also opened a “global and pan-continental window onto the future order of the world.”

Excerpted from Hitler’s American Gamble: Pearl Harbor and Germany’s March to Global War by Brendan Simms and Charlie Laderman. Copyright © 2021. Available from Basic Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.