As a synonym for a break-up note sent by a woman to a man in uniform, the Dear John letter made its debut in a major national newspaper in October 1943. Milton Bracker, a seasoned correspondent stationed in North Africa, wired a story back for publication in the New York Times magazine. “Separation,” Bracker observed, was the “one most dominant war factor in the lives of most people these days.” Regrettably, however, absence wasn’t making all hearts grow fonder. Wherever “dour dogfaces”—soldiers from “Maine, Carolina, Utah and Texas”—found themselves on the frontlines, “Dear John clubs” were springing up.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

These, the reporter explained, were mutual consolation societies formed by officers and enlisted men who’d received letters from home “running something like this: ‘Dear John: I don’t know quite how to begin but I just want to say that Joe Doakes came to town on furlough the other night and he looked very handsome in his uniform, so when he asked me for a date…'”

Yank, the Army weekly, had reported on “Brush-Off Clubs” months earlier, offering illustrative examples of these letters without yet calling them Dear Johns. Many press stories in the same vein followed, dotting the pages of both civilian and military newspapers over the course of this war and beyond. Excerpts from archetypal specimens of this newly named genre were a common feature of reportage. According to journalists, women composed brush-off notes in a variety of registers, ranging from the naively clueless to the calculatedly cruel, but invariably beholden to cliché.

Read more: The Real Biggest Myths About World War II, According to a Military Historian

When Howard Whitman explained the Dear John to readers of the Chicago Daily Tribune in May 1944, he had his imaginary female writer string hackneyed phrases together: “Dear John: This is very hard to tell you, but I know you’ll understand. I hope we’ll always remain friends, but it’s only fair to tell you that I’ve become engaged to somebody else.” Formulaic words, Whitman implied, would do little to soften the blow, while trite sentiments might even exacerbate the pain caused by a revelation that was both belated and perfunctory.

War correspondents who brought these letters to civilians’ attention were keen to preach a particular sermon about mail and morale, love and loyalty. Hyperbole was the order of the day. “It is doubtful if the Nazis will ever hurt them as much,” Whitman opined, referring to the emotional wounds inflicted by women who sent soldiers “Dear John” letters. This was quite a claim under the circumstances. Neither the loss of limbs, sight, hearing, sanity, nor death itself caused as much damage as a letter from a wife or girlfriend terminating a romantic relationship? So Whitman and others insisted.

To these commentators, it was precisely the circumstance of being at war that made rejection more tormenting—and more intolerable—than in civilian life. Since many contemporaries agreed that a broken heart was the most catastrophic injury a soldier might incur, “jilted GIs” garnered widespread sympathy, including from their COs. While the brass still tended to regard “nervousness” in combat as an unacceptable manifestation of weakness, officers often extended a pass to servicemen who responded to romantic loss with tears, depression, rage or violence.

Among other things, a “Dear John” issued servicemen a rare license to emote. That stricken soldiers would act out, and be justified in doing so, was a widely accepted nostrum in civilian circles too. Here’s Mary Haworth, an advice columnist, indignantly addressing her readership in the Washington Post in July 1944: “a bolt of bad news that strikes directly at their male ego—telling that some other man has scored with the little woman in their absence—can lay them out flat, figuratively speaking; and make them a fit candidate for hospitalization. This is no reflection on their manhood, either. It illustrates, rather, their civilized need of special spiritual nurture while breasting the demoniac fury of modern warfare.”

Read more: This Is the Best Way to Break Up With Someone, According to Experts

Like Haworth, many female opinion leaders condoned men’s emotional disintegration under the duress of a “Dear John.” Eager to shore up vulnerable male egos, they joined the chorus condemning women who severed intimate ties with servicemen as traitors—worse than Axis enemies, even, because American women were (or ought to be) on the same side.

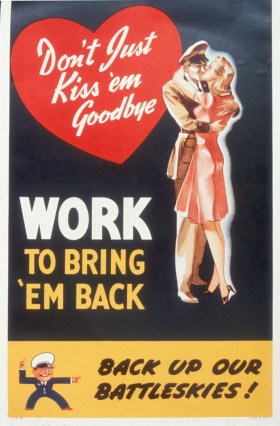

So in World War II’s gendered division of labor, it fell to women not only to wait but to write. Men battling Axis forces were fighting “for home”—as innumerable propaganda posters, movies and other patriotic prompts reminded them. Women may have symbolized the home front, but their role was neither passive nor mute. The wartime state, along with legions of self-appointed adjutants, regularly reminded women that to “keep the home fires burning,” they had to stoke the coals of romance with regular loving letters to men in uniform.

For their part, many soldiers endowed mail with magical properties. Facing the prospect of life-altering injury or death, men readily sacralized objects they believed might serve as amulets against harm. Some took this faith in mail’s protective power so literally that they pocketed letters next to their hearts, as though notepaper—or the loving sentiments committed to the page—could deflect bullets. But the magic could also work in reverse, or so some soldiers feared. For if loving letters could ward off danger, mightn’t unloving words invite it?

The Pulitzer-winning poet W.D. Snodgrass recalled harboring these suspicions as a Navy typist during World War II: “Mail call was the best, or worst, moment of each day; you approached carefully any man whose name had not been called. Only a ‘Dear John’ letter was worse—we felt, mawkishly, no doubt, that with no one to come back to, a man was less likely to come back.”

Similarly, Vietnam veteran Michael McQuiston remembers his platoon sergeant’s reluctance to let him go out into the field after he’d received a Dear John: “Their rule was that they didn’t do that. It was bad luck.” (McQuiston pestered his way into a mission only to sustain an injury, thereby confirming the wisdom of superstitious belief.)

From Homer’s The Odyssey onwards, soldiers have been haunted by—and taunted by—the specter of female infidelity, associating disloyalty with fatality. Penelope, whose constancy Odysseus put to the test by disguising himself as a beggar when he returned home after long years away at war, ultimately demonstrated her steadfastness to her husband’s satisfaction. By the time of his return, she had already fought off more than one hundred suitors with her cunningly unraveled and rewoven yarn—except in an alternative version of the legend which has Penelope sleeping with them all, as historian and archaeologist Robert E. Bell noted in his book Women of Classical Mythology.

That this revisionist myth-maker preferred not to copy Homer’s portrait of Penelope as a model of connubial chasteness hints at a larger phenomenon. Soldiers’ and veterans’ recollections have tended to accentuate the unfaithful few, not the devotedly loyal many. “Dear John” stories exemplify this trend, commonly treating as “universal” an experience that, though not unusual, was far from inevitable.

Adapted from Dear John: Love and Loyalty in Wartime America by Susan L. Carruthers. Copyright © 2022. Available from Cambridge University Press.