When Jeremy Luban first looked over the genetic sequence of the Omicron variant on his phone one day last November, it was five o’clock in the morning. But even at that hour, the University of Massachusetts virus expert knew right away Omicron was a problem.

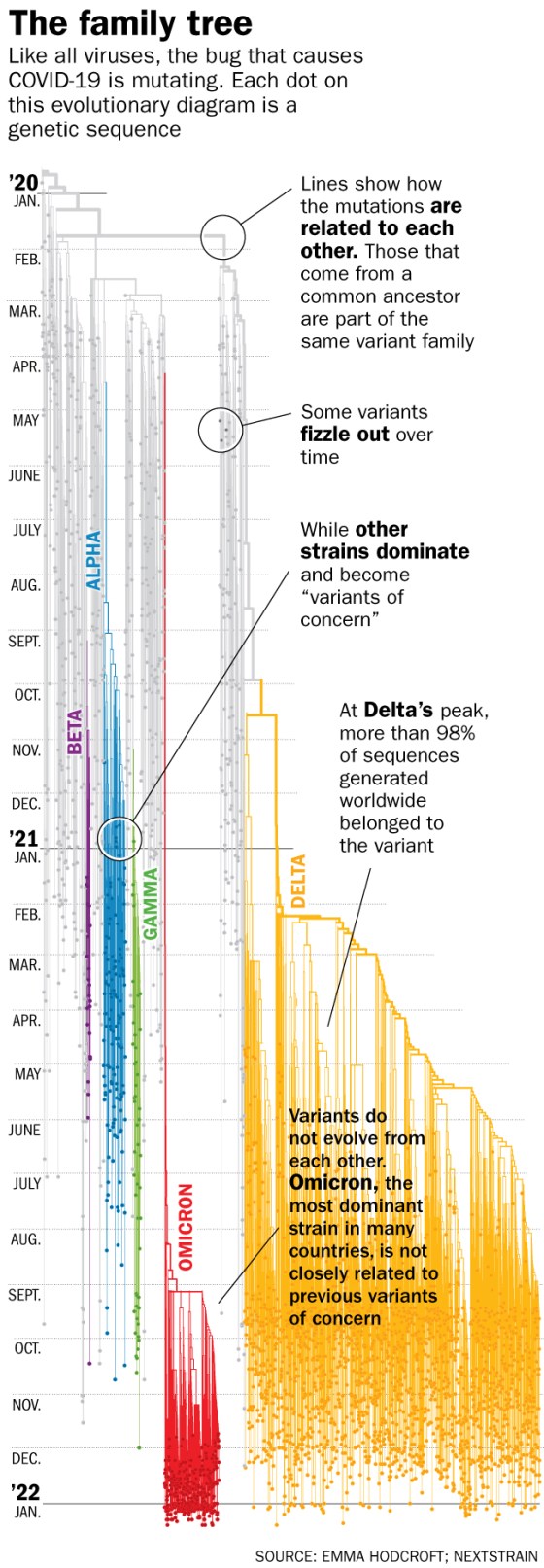

First, there was the sheer number of new mutations—by some counts, as many as 50, with 30 of them in the critical places that vaccines and drug treatments target. Second, this new version of the SARS-CoV-2 virus seemed to appear out of nowhere, unpredictably and with no immediately obvious connection to previous variants.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

“It’s like when you look at the first page of a comic book and all of the Marvel villains have gotten together,” he says. “That was literally what it was like when I saw the sequence. How are we going to survive this? We can deal with one [mutation], but 10 or more of them all at once?”

Other public health officials shared Luban’s alarm, but, it turns out, Omicron, like all villains, has an Achilles’ heel. For people who are vaccinated or who have been exposed to its predecessors, this variant does not seem to cause severe disease. While it can still be dangerous for people who are unvaccinated, or who have health conditions that make them more vulnerable to COVID-19’s effects, for the vaccinated, there was a glimmer of hope.

Whether justified or not, that glimmer has been flamed into a blazing beacon by some people, who interpret Omicron’s relatively mild effect on health if you’re vaccinated—a sore throat, some flu- or cold-like symptoms, or no noticeable symptoms at all—as a sign that SARS-CoV-2 may be reaching the end of its onslaught. If Omicron isn’t as virulent, then SARS-CoV-2 must be weakening, the thinking goes.

Even leading scientists have been tempted by the idea, admitting that of all the versions of SARS-CoV-2 that have hit humanity over the past two years, Omicron might be the preferable one to get infected with, since it doesn’t make the immunized that sick. And if more vaccinated people are infected with Omicron and develop immunity, that protection, combined with the protection that some people might have from being infected with previous variants, could reach the magical herd immunity threshold—which experts say could be anywhere between 70%-90% of people recovered from or vaccinated against COVID-19—that would finally make SARS-CoV-2 throw up its spike proteins in defeat.

Read more: No, You Should Not Try to Get Omicron

According to some models, by the time Omicron works its way through the population, up to half of people around the globe will have been infected, and presumably immune to the variant. With fewer unprotected hosts to infect, viruses generally begin to peter out—epidemic influenza viruses are a good example—and optimistic models show that after a peak of cases by the end of January and beginning of February, SARS-CoV-2 may follow that path. Under that assumption, COVID-19 would begin its shift from being a pandemic disease to an endemic one, confined to pockets of outbreaks that erupt among immunocompromised populations or the unvaccinated, such as the youngest kids—but are manageable and containable because most people would be protected from the worst effects of the virus.

But there’s also the possibility of a darker timeline, in which the unpredictable nature of SARS-CoV-2 to date drives the next year and beyond. If that occurs, it could mean the sobering possibility that Omicron is not the beginning of the end, but just the beginning of a more transmissible, more virulent virus that could do even more harm than it has already.

Scenario #1: The COVID-19 virus has achieved equilibrium with humans

Let’s start with the more sanguine prediction of what 2022 might hold for SARS-CoV-2.

There are several lines of scientific evidence that support this perspective, including some long-held truisms about how viruses behave as they find more hosts to infect.

Viruses mutate every time they make copies of themselves, becoming more or less infectious, or more or less harmful to their hosts. For a changing virus, it’s all about balance; finding the right mutations that allow it to become more efficient at spreading from one host to another in order to infect cells, while not causing so much disease that the host dies. A dying or dead host won’t help it to keep replicating.

Textbooks teach that viruses, being the relatively simple entities that they are, have limited resources to devote to their one goal: survival. A virus can’t even reproduce on its own, and needs to borrow the reproductive machinery of cells from those that it infects. So, when a genetic mutation makes a virus more adept at spreading from one host to another, with each new host a brand new virus-making factory, it’s a huge advantage. It also suggests that the virus is opting for transmissibility over virulence; it’s in its best interest to spread more quickly and replicate than in causing its host to die.

Omicron appears to be the perfect example of that strategy. What Luban saw in the virus’s genetic sequence last November was a series of changes that made the variant at least several-fold more transmissible than the previous one, Delta, which was already twice as transmissible as the original version of SARS-CoV-2. Such high transmissibility led to Omicron’s quick dominance across the globe—replacing the previous variant, Delta, in a mere two months. “The speed with which Omicron took over was really amazing,” says Shangxin Yang, assistant professor of pathology and laboratory medicine at University of California Los Angeles. “It’s almost magical. In two weeks, it went from accounting for 1% of COVID-19 cases around the world to 50% of cases, and in one month, to almost 100% of cases. That’s amazing speed; we could never have imagined any virus could do that.”

Yang points to other lines of evidence that suggests Omicron’s high transmissibility may herald SARS-CoV-2’s last hurrah. Whereas all previous variants of the virus preferentially infected cells deep in the human respiratory tract, nestling all the way into the lungs, Omicron tends to infect the cells in the upper respiratory tract. That makes it more like the common cold, and could explain why, at least among the immunized, Omicron tends to cause milder disease than previous variants.

Read more: What Actually Worries U.S. Doctors About Omicron

Those early versions of SARS-CoV-2 also tended to cause a phenomenon called cell fusion, in which a virus infects one cell, then co-opts other viruses that have infected other cells to fuse into a large viral mass to make a larger virus-making machine. That’s good for the virus, but bad for the patient, as it can trigger inflammation, which can in turn destroy cells and tissues; such inflammation is the hallmark of late-stage, severe COVID-19 disease. Omicron doesn’t lead to such cell fusion and therefore tends to cause less cell damage, which could in part explain, at least in immunized people, why those infected with Omicron tend not to get as sick. Recent data from the U.K. shows that vaccinated people infected with Omicron are two-thirds less likely to be hospitalized than vaccinated people infected with Delta.

“All of this comes together to make the perfect scenario to end the pandemic,” says Yang. “This is exactly how most other pandemics with respiratory pathogens had ended. They spread like fire and then eventually most people either became vaccinated or infected and when the population reached herd immunity, the pandemic ended.”

That doesn’t mean it’s the end of SARS-CoV-2, but it could signal the end of its pandemic phase. From there, COVID-19 should shift into being endemic, in which we learn to live with a virus that has already learned to live with us.

Read more: We Need to Start Thinking Differently About Breakthrough Infections

At this stage, says Yang, “the virus has already accomplished its goal of establishing a balance with its host—humans. It can spread easily among hosts, but not kill them, so it lives among its hosts. The virus has mutated to the point where it just chooses to live among us without causing too much trouble. And in return, we have to learn to live with the virus as if it is just another common cold.”

That’s not just wishful thinking, he says—there’s historical precedent. Already, there are four coronaviruses that have been circulating among us for decades causing mild symptoms similar to the common cold. At some point in history, these coronaviruses could, hypothetically, have burned through the world’s population like SARS-CoV-2 is currently, and then, as more people became infected and therefore protected, these viruses could have become endemic and happy to cause infection where it could, among vulnerable people with weakened immune systems.

“One of these now-common cold coronaviruses may have been responsible for an epidemic in the late 1800s that back then did not cause such mild disease,” says Nadia Roan, an associate investigator at the Gladstone Institutes. “But eventually as community immunity started to build, it became more endemic. It makes sense that—hopefully, potentially—Omicron could become one of the common coronaviruses when we as a community build up enough immunity against it.”

Scenario #2: The virus could keep changing in unpredictable and possibly deadly ways

But a different, troubling scenario might also be possible. There is good evidence that suggests SARS-CoV-2 is an especially unpredictable virus—Omicron, after all, was an entirely new variant that shocked experts with its sudden and efficient ability to spread so quickly. In the fall of 2020, most virologists would have made an educated guess that if a new variant of SARS-CoV-2 were to emerge, it would be a souped up version of Delta—there was even talk of a Delta Plus. But Omicron surprised them all.

“This isn’t a Delta-plus variant,” says Jeremy Farrar, president of the global health research foundation Wellcome Trust. “It’s from left field, and came out of a virus from 2020, which tells us something. We haven’t seen one lineage of this virus evolving into another lineage. We’ve seen things coming from a much broader spectrum. What that means is that we can’t expect the daughter or son of Omicron to then become the next thing we deal with. It could be something that comes from a different part of the virus’s evolutionary path.”

What that suggests is that if we want to be prepared for future, potentially dangerous variants, we need to more closely monitor the virus around the world so we can identify any possibly highly transmissible variants earlier, and hopefully control them better.

Read more: What We Learned About Genetic Sequencing During COVID-19 Could Revolutionize Public Health

And as surprising as it was, Omicron probably didn’t appear overnight. SARS-CoV-2 likely evolved in stages, and the increasing transmissibility of what would become the Omicron variant went largely unnoticed. For example, about a year ago, researchers reported what should have been alarming changes to SARS-CoV-2 in three air passengers flying from Tanzania who tested positive for the virus when they landed in Angola. Those changes helped the virus evade the immune system better, and transmit more efficiently. Looking back, while their viral sequences did not quite match that of the variant we now know as Omicron, they showed enough worrying signs of adaptation to human immune defenses that we should have taken stronger action to contain those cases.

“There is no reason to think that Omicron is the result of the virus mutating any faster,” says Luban. “It’s just that we never saw this version as it was developing, wherever that was.” That may have been in someone with a weakened immune system, who was only able to mount a partial defense against the virus, which was just enough selective pressure to push the virus to mutate, and continue mutating, until it hit upon the changes that helped it to become the efficiently spreading virus we now know as Omicron. Since the pandemic began, scientists have reported on cases of immunocompromised patients who have been able to harbor potentially mutating viruses for months or even a year.

In other words, the next Omicron could already be out there, and we wouldn’t know it.

Unless, that is, we dramatically improve our global surveillance efforts, and increase the amount of genetic sequencing of the virus that is done around the world. Laying bare the virus’s genome can provide the earliest hints of any changes, and clues as to which of these aberrations could be dangerous for human health.

If we’d been able to identify the genetic changes that led to the Delta variant early on, for example, we could have prioritized locking down the parts of the world where those mutations were common, says Pardis Sabeti, professor at the center for systems biology at Harvard and member of the Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT. “That’s what genomic sequencing can do—stay ahead of diagnoses [of new cases] so we can try to develop countermeasures against something, including developing new therapies. It’s about ‘know thy enemy.’ If your enemy moves, you have to move.” With real-time genetic information, we could better know how to prioritize vaccine and treatment efforts. “The more information you have, the more thoughtful we can be in expending what are necessarily finite resources,” says Sabeti.

Read more: Let’s Not Be Fatalistic About Omicron. We Know How to Fight It

The problem, as Sabeti and Luban note, is that we don’t have such genomic eyes on the virus throughout the globe. Even in the U.S., where sequencing is becoming a priority, the Centers for Disease Control’s National SARS-CoV-2 Strain Surveillance program is sequencing only a small percentage of positive cases—in the single digits—each week. Only about five countries have sequenced double digit percentages of their positive cases so far.

Experts’ best guesses at what comes next

How likely is it that Omicron is indeed SARS-CoV-2’s last hurrah? Farrar puts the odds at 40% to 50%.

One major reason the odds aren’t higher is that Omicron’s genetic changes make it more capable of evading capture by the antibodies the immune system makes, both after natural infection and vaccination. That helps the virus to spread more quickly—up to the tipping point at which if the virus is too good at spreading and causing disease, then it becomes self-defeating.

“The virus doesn’t want to kill its host,” says Dr. Warner Greene, former director of and current senior investigator at the Gladstone Institute of Virology. “That’s counterproductive.” That could explain why Omicron is so impressively transmissible, but, for those with some protection, especially from vaccines, not particularly dangerous—making it possible that this particular version of the virus is the one that will persist in the human population for years and years to come.

That’s the path public health experts hope SARS-CoV-2 will take, following the example of the other common coronaviruses. “The best scenario is for the virus to become so weakened it just becomes a vaccine itself,” says Greene. “It would spread but it wouldn’t cause severe disease. In that kind of setting, the virus would start to lose its foothold and become endemic in very small areas, replicating only when it finds people who are not previously infected or vaccinated.”

That’s assuming, of course, that most of the world’s population is vaccinated, or recovered from being naturally infected with Omicron. The fewer opportunities SARS-CoV-2 has to replicate and produce more copies of itself, the fewer people will become infected, and the fewer people will get sick. Every variant in the virus’s short two-year history is the direct result of unchecked viral replication, so the surest way to turn COVID-19 from a pandemic into an endemic disease is to shut down as many of those opportunities as possible. “If we have learned anything from the past year, it is that variants will continue to emerge,” says Dr. David Ho, director of the Aaron Diamond AIDS Research Center and professor of microbiology and immunology at Columbia University. “What will be helpful is to establish growing immunity, either from vaccines or infections. That will help protect the population from the next one.”