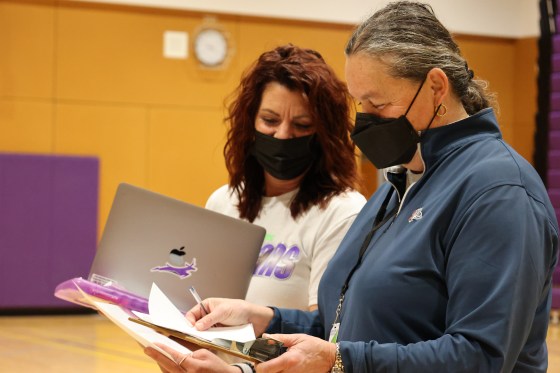

As a school superintendent, Michelle Reid’s job description includes managing the district’s budget, supervising school staff and making big-picture decisions. But lately, she’s been returning to her former roles of teacher and coach, filling in for absent educators in the face of a national shortage of substitute teachers.

On Nov. 12, she stepped in to teach a high school physical education class. She’s expecting to teach middle school math in the weeks ahead. Other school administrators, principals and teachers are filling in wherever they can as well.

<strong>“It’s an all-hands-on-deck process.”</strong>“All of our central district office staff who are able to be certified to teach are helping out in our schools,” says Reid, superintendent of the Northshore School District in Bothell, Wash. “All classes, all grade levels.”

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

She says the district has recently been able to find substitutes to fill in for 80% to 85% of absent teachers on any given day, leaving the rest of the vacancies up to existing staff to cover: “It’s an all-hands-on-deck process.”

“Teachers have had to step in and teach all day without planning periods, which requires them then to do planning later into the afternoons and evenings, which honestly has created a sense of fatigue among many of our staff members,” Reid says.

Read more: From Teachers to Custodians, Meet the Educations Who Saved a Pandemic School Year

It’s the latest example of how the pandemic has exacerbated the already formidable challenges of running a school district. When teachers are absent due to illness, COVID-19 exposure or other routine reasons, school leaders are finding it more difficult to get someone to take their place.

More than 75% of school principals and district leaders said they were having trouble finding enough substitutes to cover teacher absences this year, according to a national EdWeek Research Center survey published in October. More administrators reported challenges hiring substitutes than any other school position, including bus drivers, paraprofessionals, full-time teachers and custodians.

Some school districts have had to close for a day due to the staffing shortages. On Nov. 12, the school district in Kent, Wash., was one of them. “During the pandemic, our staff, at every level, has experienced an unprecedented amount of stress, impacting their mental health,” interim Kent superintendent Israel Vela said in a statement. “Unfortunately, we cannot safely operate schools with the staff and substitute shortages we are already seeing in our data.”

Low pay, high risk

In many ways, the trend has been driven by the pandemic. Like all educators, the job of a substitute teacher has become more fraught during the past two years. They are called upon to teach in schools where children are likely still unvaccinated and might not be required to wear masks. In some cases, they’re filling in for teachers who are quarantining at home after being exposed to COVID-19. And many substitute teachers are in an age group that is more vulnerable to the disease.

“A number of our substitute teachers are retired educators, and in many cases, they simply are not willing to risk the COVID challenges to come to work,” Reid says.

But the shortage of substitute teachers also preceded the pandemic in many places, as they face low pay, unpredictable schedules and the challenge of supervising students who might misbehave in the absence of their teacher. The median hourly wage for short-term substitute teachers is $14.12, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Some school districts recently raised pay for substitute teachers to encourage more people to take on the job. The Jordan School District in West Jordan, Utah gave substitute teachers a $7 hourly wage increase and also started offering bonuses of up to $500 depending on how many days they work this semester, the Salt Lake Tribune reported.

The Fairfax County School Board in Virginia voted in October to raise substitute pay by $1 to $3 per hour. “We’ve at least got to make sure people can put food on the table when they come to our rescue,” Laura Jane Cohen, a member of the Fairfax County School Board, told local news station WTOP.

In North Carolina, the Wake County school board voted Tuesday to raise substitute pay to $130 per day for those with a teaching license and $104 per day for those without one. “We all know this is long overdue for our substitute teachers,” school board vice chair Lindsay Mahaffey said, according to the News and Observer.

Read more: ‘I Work 3 Jobs and Donate Blood Plasma to Pay the Bills.’ What It’s Like to Be a Teacher in America

More from TIME

Changing requirements to fill the gaps

Others have responded by changing the requirements to become a substitute. In October, Oregon created an emergency substitute teacher license, loosening requirements in response to “severe staffing shortages.” While the state had 8,290 licensed substitute teachers in December 2019, that number had fallen to 4,738 in September 2021.

<strong>“A number of our substitute teachers are retired educators, and in many cases, they simply are not willing to risk the COVID challenges to come to work.”</strong>“Without additional teachers, classes will be combined to unacceptable levels or not offered at all, inflicting irreparable harm on schoolchildren,” state officials wrote in the order establishing the emergency license. “These rules significantly expand the pool of potential teachers districts may use to address the most critical shortages and give them desperately needed tools to fill openings that cannot be filled in any other way.”

But merely lowering teaching qualifications is a solution that worries some education experts, who would like to see systemic changes that make the profession more desirable and competitive long-term.

“Lowering the standards for substitutes to the point where you’re not getting people skilled or knowledgeable in the content area, is really problematic,” says Linda Darling-Hammond, president and CEO of the Learning Policy Institute, noting that teachers have long been underpaid compared to similarly educated peers.

“Schools, districts and states — because a lot of this is state responsibility — need to be rebuilding the teaching profession in a way that offers a salary that is competitive with other jobs that a person with that level of education could get.”