Now that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has recommended Pfizer-BioNTech’s COVID-19 vaccine for kids aged 5 to 11, the Biden Administration has signaled that it will rely on a “trusted messenger” to get information to parents and provide access to vaccines: schools.

As part of the plan to deliver COVID-19 vaccines to the youngest population yet, schools will again take on a role they’ve assumed during health crises throughout American history: promoting vaccination to keep kids and communities safe from infectious disease. “Schools have probably been the most important agent of the U.S. being a highly vaccinated population,” says Richard Meckel, a professor of American studies at Brown University. According to experts on vaccination history who spoke with TIME, efforts to fight past childhood scourges—such as polio, smallpox and diphtheria—highlight the important role schools can play. But there are also lessons to be gleaned about what happens when parents and public health officials disagree.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

Given that October polling suggests only 27% of parents who have kids aged 5 to 11 intend to get their children vaccinated right away—while 30% say they will “definitely not” have their child vaccinated—it’s clear that vaccine proponents have little room for error if they want to win over nervous parents.

A Responsibility for Kids

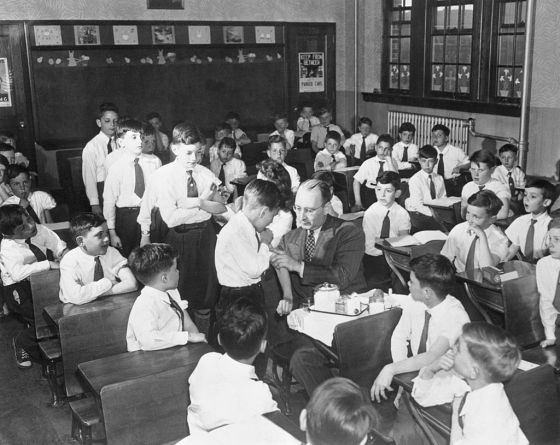

In the 19th century, viruses were ever-present but poorly understood. About one-fifth of children died before reaching age 5, many from infectious diseases such as diphtheria that are now preventable with vaccines. However, that began to change in the late 19th century in tune with growing awareness that disease spread not through mysterious “miasmas” (a theory that emanations from decaying things cause infectious disease) but via person to person. According to Meckel, this led to a growing concern: how did infectious disease spread in schools? The public had good reason to worry. Classrooms were often crammed with as many as 60 kids, who sometimes had to rely on “terribly smelly” latrines in poorly ventilated basements, Meckel says. Exposés about conditions at schools fanned public outrage about the way kids were being treated—as well as concerns that schools could be incubators for infectious disease.

There was also a mounting push for the government—especially in states and municipalities—to get more involved in public health, especially as school days lengthened and communities began to make education compulsory, says Meckel. Over time, schools invested in efforts like physical education, fire safety and the containment of infectious disease. They were increasingly empowered to take steps to control diseases, by refusing to teach infectious children, or, starting with Massachusetts in the 1850s, requiring vaccination. While community members sometimes organized to fight the rules, even filing litigation, the courts mostly backed schools up. In 1922, for instance, the Supreme Court ruled in Zucht v. King that states had the right to require kids to be vaccinated to attend school in order to protect public health. Essentially, says Meckel, this ruling revolved around a big idea: “[states] have the right to deny access to schools to protect the public health.”

The influence of this idea is still present in the form of modern vaccine requirements and laws. All 50 states now have vaccine requirements for students, and six of them, including New York and California, do not permit religious or personal exemptions from the mandates. During the COVID-19 pandemic, schools’ role in protecting public health is visible in states’ decisions to require precautions to keep children safe, such as face masks, remote schooling and vaccine requirements for teachers. But while schools’ right to enforce strict measures to keep kids safe has a long-standing precedent, it may come into question in the coming months, if states or municipalities decide to impose a vaccine mandate for COVID-19.

A Great Way to Reach Children

School mandates and educational programs have played a major role in the fight against many infectious diseases—including smallpox, diphtheria and measles—but one of their greatest successes was the elimination of polio in the U.S, which paralyzed 35,000 people a year in the late 1940s, according to the CDC.

Schools were directly involved with the polio vaccine from the very beginning. In 1954, hundreds of thousands of first-, second- and third-grade children were injected with placebos or a polio vaccine developed by the virologist Dr. Jonas Salk. Teachers and principals volunteered to assist these trials, sorting children’s records, gathering consent forms and organizing clinics where kids could get vaccinated at free—some of which took place at schools. Teachers worked with health departments to develop lessons on vaccines, even incorporating coloring books, says Colgrove. While there were about 15,000 cases of paralysis caused by polio each year in the 1950s, that dropped to fewer than 10 by the 1970s. Since 1979, no cases of polio have been contracted in the U.S, according to the CDC.

The polio vaccination effort illustrates the importance of parents’ support for vaccination efforts, says James Colgrove, a professor of sociomedical studies at Columbia University. Part of the reason it was so successful, he says, was that in the post-World War II era, the public had much greater trust in institutions than they do today, including in science; this was stoked by major advancements such as penicillin, which was put into mass-production in the 1940s. Colgrove contrasts that with the rollout of the HPV vaccine in the 2000s, when public opposition derailed some efforts to make it mandatory in schools.

“One lesson learned is that any effort that’s centered around schools has to be very mindful of the need to communicate with parents, to engage parents, as much as possible,” says Colgrove.

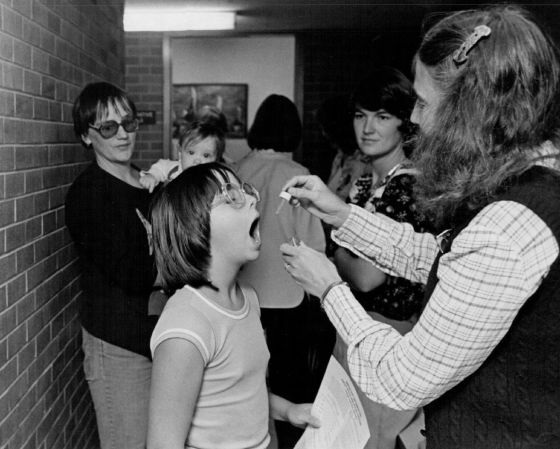

The 1977 Childhood Immunization Initiative, which aimed to identify kids missing a childhood vaccination and raise kids’ vaccination rate for the standard childhood vaccines to 90%, also illustrated schools’ potential to promote vaccination, Colgrove says. About 28 million school records were reviewed to identify kids who were missing a shot and refer them for vaccination. By the fall of 1980, the vaccination rate among kids enrolling in school was 96% for measles, rubella and diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis; 95% for polio; and 92% for mumps.

As Colgrove notes, however, the program highlighted how ill-prepared schools were to promote vaccination. The initiative was supported with millions of dollars of funding, which some schools would not have been able to replicate alone—especially the ones in poorer districts, with students more vulnerable to infectious disease. “I think what that episode demonstrated was just how time and labor intensive it is for schools to fulfill this role,” says Colgrove. “Ideally, the school districts could then really be the perfect place to reach those kids. But the way we fund public education in this country is through property taxes. And so the inequity compounds the existing situation that put those kids at risk in the first place.”

Reaching low-income kids in poorly resourced schools will be a major priority during the COVID-19 pandemic, especially given that lower income families tend to face more barriers to vaccination. Half of parents with a household income of less than $50,000 say that they’re very or somewhat concerned about taking time off to get their child vaccinated or to care for them if they experience side effects, compared to 23% of families with higher incomes, according to Kaiser Family Foundation polling from October. The Biden Administration has proposed efforts to make vaccines more accessible, including providing them on campus, and ensuring vaccines are available after school, in the evening and over the weekend.

Inevitable Opposition

American opposition to vaccination is nearly as old as vaccines themselves. In 1722, an opponent threw a small bomb through the window of a Boston home belonging to Rev. Cotton Mather, who was responsible for helping to introduce an early smallpox inoculation to the United States. A note on the bomb read, “‘Cotton Mather, you dog, dam you! I’l inoculate you with this; with a pox to you’’ [sic].

Today, public opposition to vaccines has sometimes blocked efforts to mandate them in schools. After the vaccine Gardasil was approved in 2006 to limit the spread of the human papillomavirus (HPV), a sexually transmitted infection that can lead to cervical cancer, experts recommended it for young adolescents in an effort to protect them before they became sexually active. However, as legislatures introduced bills to mandate the vaccine in schools, it faced a swell of opposition from parents—with some arguing that it didn’t make sense to issue a school vaccine mandate for a disease that doesn’t spread in schools. Ultimately, most efforts to mandate the vaccine failed. According to the Immunization Action Coalition, only three states and the District of Columbia now mandate the HPV vaccine.

Some communities and states have signaled that they’re considering vaccine mandates for COVID-19 in public schools, but legal challenges and protests against mandates for adults—such as the lawsuit filed against New York’s mandate for teachers—seem inevitable, and some school districts are already the subject of legal challenges. San Diego Unified School District, which was one of the first school systems to issue a mandate, is facing a suit from a student who claims that receiving a vaccine would violate her religious beliefs.

When it comes to the COVID-19 vaccination effort, Colgrove says, history suggests that while schools have “tremendous potential to be sites to achieve high vaccination levels,” they’re also “potentially politically explosive.”