Scotland could be one step closer to becoming an independent country.

The British government has been forced to play defense on calls for a second Scottish independence referendum, after the country’s main nationalist party secured an emphatic victory in elections for its devolved parliament on Friday.

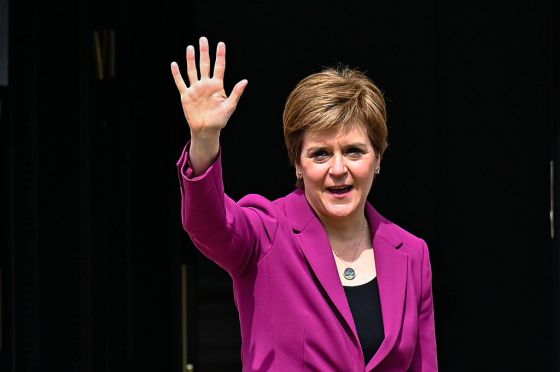

“The question of a referendum is now a matter of when, not if,” Scotland’s leader Nicola Sturgeon told British Prime Minister Boris Johnson on a phone call following the election results, her press office said in a statement.

But the power to grant Scotland an independence referendum lies in London, not Edinburgh, and Johnson pushed back against the idea on Saturday, calling it “irresponsible and reckless.”

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

So just how likely is a new Scottish independence referendum?

What were the results of the election in Scotland?

Together, pro-independence parties won a majority in the Scottish Parliament in elections on Friday.

Sturgeon’s Scottish National Party (SNP) won 64 seats, one more than at the previous election, but one short of an overall majority. The Scottish Greens, who also support independence, won eight seats.

In its pre-election manifesto, the SNP pledged to hold a new Scottish independence referendum “after the COVID crisis is over.”

“This election is most immediately about the need to steer the country safely through the rest of the pandemic,” Sturgeon said ahead of the vote. “But it is also about the longer term job of rebuilding and recovery that is needed, and who is best placed to lead that.”

Why is the Scottish National Party seeking independence?

Scotland has already had one independence referendum, in 2014, in which Scots voted by a margin of 55% to 45% to remain part of the United Kingdom. The British government agreed to hold that referendum after the SNP won a majority in the Scottish Parliament, calling it a “once in a generation” event.

But support for another referendum has steadily risen in the years since 2016, when the U.K. voted to leave the European Union, a move opposed by more than 62% of Scottish voters.

Read more: The U.K. Has Officially Left the European Union. But Could Scotland End Up Back in It?

After the Brexit referendum, the SNP argued that Scotland was being pulled out of the E.U. against its will and that this “material change in circumstances” justified another vote on Scottish independence.

What happens next?

While the SNP has pledged not to hold a new independence referendum until after the COVID-19 crisis is over, it “has been relatively clear about its immediate next steps,” says Akash Paun, manager of the devolution research program at the Institute for Government, a London-based think tank.

At the top of the party’s independence to-do list is formally requesting permission from the U.K. government to hold a new independence referendum, by passing what’s known as a “Section 30 order” under the Scotland Act—the same mechanism that it used to bring about the 2014 referendum.

It needs to do this because, even though the Scottish Parliament has a suite of its own devolved powers, the British Parliament in Westminster still controls legislation over “constitutional matters.”

“The SNP are going to argue that they have a clear mandate and a manifesto commitment to do this, and that they and their allies have won a majority—and that it would be democratically illegitimate for the U.K. government to simply say no,” says Paun, adding that the appeal to democratic legitimacy is a political argument rather than a legal one. “Does the SNP have any way to compel the U.K. government to pass such legislation now? Of course they don’t.”

Most analysts expect Johnson, who has publicly opposed the idea of another Scottish independence referendum, to refuse a request to hold another one. The next step for the SNP would be to bring forward its own bill in the Scottish parliament calling for a referendum, “even if they don’t have authorization from Westminster to do so,” says Paun. This would likely pass with the support of the pro-independence parties in Edinburgh, he says.

That would lay the ground for a contentious battle at the Supreme Court in London, which would be forced to rule on whether the Scottish Parliament had the authority to call a referendum on its own. “Indications are, it’s quite likely the Supreme Court would block it,” Paun says.

How likely is another independence referendum?

In the near-term, another referendum is probably not very likely. But if Scottish nationalists continue to dominate the country’s parliament, it might become harder for U.K. leaders to deny requests for another vote.

Sturgeon’s SNP has long focused on winning the “political argument” for independence, insisting that the legal argument will flow from that. Now, the British government is attempting to win the political argument for union.

Johnson has set up a “union unit” at his 10 Downing Street office, and observers predict his Conservative government will launch a ramped-up PR campaign focused on the benefits of U.K. public spending in Scotland. “It’s more of a longer game: can you persuade enough voters and public-opinion formers in Scotland that the Conservatives in Westminster are not hostile to Scotland?” Paun says.

What would Scottish independence mean for the rest of the U.K.?

The government reportedly fears that if Scotland were to become independent, it could precipitate a broader breakup of the U.K.

Next on the cards, they fear, could be Northern Ireland, which also voted to remain in the E.U. in 2016, and where support is rising for reunification with the Republic of Ireland, which is an E.U. member state.

“Scotland is going to be the generational decision, probably in the next five-to-six years and possibly even before that, depending on what happens there,” Peter Cardwell, a former special advisor to two U.K. government Northern Ireland secretaries, told TIME in April. “If Scotland becomes an independent country, then a united Ireland is probably inevitable.”

Read more: Northern Ireland Is Experiencing Its Worst Violence in Years. What’s Behind the Unrest?

Still, as much as the “hard” version of Brexit delivered by the Johnson-led government has increased the popularity of nationalism in Scotland, it has also made the prospects of leaving the U.K. more difficult, particularly if an independent Scotland wished to rejoin the E.U. The effects would be felt hardest in areas close to the border, where seamless cross-border trade with England would be at risk from trade checks between the two countries.

Tellingly, in Friday’s elections, all Scottish constituencies sharing a border with England elected lawmakers from the Scottish Conservatives, who oppose independence.

“The ironic thing about Brexit is that it made it easier for the SNP to argue for independence on democratic grounds,” says Paun. “But it makes the economic argument for independence much more difficult.”