As workers continue to comb beaches for tar balls in California’s Orange County after an underwater pipeline ruptured on Oct. 2, another massive fossil fuel cleanup operation is just getting underway on a 55-year-old rig anchored 120 miles up the coast. It’s a taxpayer-funded, $60 million debacle that reveals just how difficult and costly it may be to shut down aging oil rigs in the Pacific Ocean and decarbonize the country’s energy supply.

Anchored two miles off Santa Barbara, the rig in question, known as Platform Holly, was built by ARCO in 1966, sold to Mobil in 1993, then sold again to a small Colorado-based oil company called Venoco in 1997. In 2015, a corroded onshore pipeline carrying crude oil from Holly and other nearby platforms burst, hemorrhaging oil onto the beach and into the Pacific Ocean. With the pipeline shuttered, Venoco declared bankruptcy in 2017, abruptly notifying California authorities that it would be abandoning its lease and letting its rig workers walk off the job. Faced with the risk of another leak from the abandoned rig, the California State Lands Commission had no choice but to take over the platform.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

The situation turned out to be even worse than it seemed. A $22 million bond Venoco previously put up—essentially a security deposit intended to cover the costs of exactly this situation—was only enough to fund just 6% of the approximately $360 million needed to plug Holly’s 30 oil wells and properly decommission the rig. Venoco wasn’t “managing maintenance the way they should have” during Holly’s last years of operation, according to Seth Blackmon, chief counsel of the California State Lands Commission, which meant that pressurized gases and oil were leaking into an outer containment zone around the platform’s wells. The state was forced to continuously pipe a mixture of seawater, crude oil, and highly poisonous hydrogen sulfide gas from the leaking wells to Venoco’s onshore processing facility, which separates the components and incinerates the hydrogen sulfide. ExxonMobil, Holly’s previous owner, agreed to shoulder the cost of plugging the wells and decommissioning the structure, which would cost about $300 million, but the additional price of continuously off-gassing Holly’s hydrogen sulfide, running the processing facility and maintaining the half-century-old oil platform in a safe condition until it could be decommissioned fell onto the state.

That decommissioning work, which began in late 2019, was paused for a year and a half due to COVID-19; work capping the wells restarted only last week. In the meantime, California paid between $750,000 and $1 million every month to maintain Platform Holly and deal with its poisonous emissions, a cost that, since 2017, has added up to $64 million. The State Lands Commission expects to finish plugging all 30 of Holly’s wells within the next 16 months, according to Jennifer Lucchesi, the agency’s executive officer, but further delays are possible—and the state will pay an additional $1.5 million a month while the work is underway.

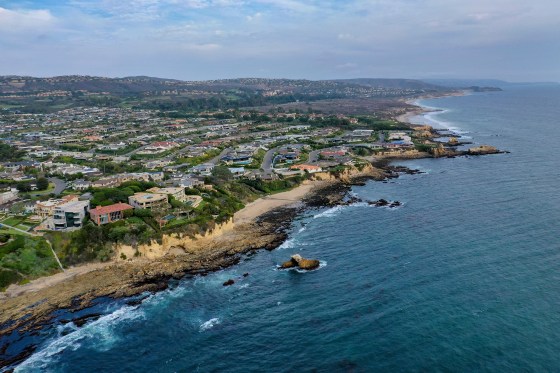

Platform Holly’s long-running shutdown fiasco was put into sharp relief this week, after tens of thousands of gallons of oil spilled from a fractured underwater pipeline off the coast of Orange County. The spill, which has shuttered beaches and caused untold ecological damage, has reinvigorated calls to remove oil infrastructure from California’s coasts. “It’s time, once and for all, to disabuse ourselves that this has to be part of our future,” California governor Gavin Newsom said at an Oct. 5 news conference.

California hasn’t issued any new leases in state waters for 50 years, a precedent established after a disastrous 1969 oil spill off Santa Barbara. In federally-controlled waters off California, which begin three miles offshore, no new leases have been issued for more than three decades. The Trump Administration made moves to reopen those areas to drilling in 2018, though California state legislators passed measures that would have made it difficult for any potential new oil platforms to operate, and courts ultimately blocked the Trump proposal. A bill introduced in Congress this past January by California Sen. Dianne Feinstein and California Rep. Jared Huffman proposes to permanently ban federal offshore leases off the coast of California, as well as off Oregon and Washington.

But for Californians who want to end periodic fossil fuel disasters off their coasts and draw down the state’s carbon emissions, such a ban wouldn’t address the root of the problem: the 26 aging oil rigs in state and federal waters on California’s continental shelf. Opponents say those rigs and their pipelines, many of them still operational years beyond their planned life-spans, are disasters waiting to happen. “When there’s drilling, there will be spilling,” Alan Lowenthal, a Democratic House representative from the area affected by the Orange County spill, said on Oct. 5, speaking alongside Newsom. “We have to come up with a plan to not only stop new drilling, but to figure out how do we stop all drilling that’s going on in California.”

Newsom has said he wants to end drilling—offshore and on land—in California by 2045, while the U.S. Interior Department’s Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement announced this July that it was working on a decommissioning process for eight defunct oil platforms on expired federal leases off the California coast. But as the Platform Holly debacle shows, getting rigs out of west coast waters may be harder than it seems. There are currently 15 other rigs in federal waters, and three more in state waters, and there’s no easy way to get them out of the oceans, since their original leases often give their owners the right to continue operating as long as the platforms are pulling up oil. When their leases are up, offshore oil companies are usually required to pay the full cost to cap their oil wells, disassemble their rigs, and restore the seafloor to its prior condition.

But that expensive obligation doesn’t kick in until the underground reservoirs functionally run dry, so companies tend to keep pumping for as long as they can. “They would prefer to defer that cost as long as possible,” says Greg Rogers, an attorney and accountant who studies oil infrastructure decommissioning. “Forever, if possible.” Sometimes oil companies pass off those obligations like a hot potato, with fossil fuel giants like ExxonMobil selling offshore rigs on partially depleted fields to smaller “wildcat” operators like Platform Holly’s Venoco, which try to extract as much money as they can out of the leftover assets. When the decommissioning bill comes due, those small companies can declare bankruptcy and let taxpayers clean up their mess, as Venoco has.

Some environmentalists say state and federal governments should cancel oil companies’ leases outright. But such moves would inevitably wind up in court, where public attorneys would likely have to prove that each individual rig in question is threatening citizens’ health and safety, says Rob Schuwerk, an attorney and executive director of Carbon Tracker North America, which studies fossil fuel investments and climate change. “I would imagine that would be difficult,” he says. In California, Lucchesi, of the State Lands Commission, says it would likely be illegal for her agency to end existing oil leases. Yanking leases out of oil companies’ hands would require new legislation, and the tactic would leave California open to massive lawsuits. “[Oil companies] do have a vested contractual right in these leases,” she says.

Some advocates say that battle is worth fighting. “They are taking risks with the whole state’s economic well being, and that’s not even counting human health,” says Richard Charter, a senior fellow at The Ocean Foundation. Robert Hertzberg, who leads the Democratic majority in California’s State Senate, has proposed a softer tactic: modifying a 2010 “Rigs-to-Reefs” law to change the underlying incentives at play. The law allows oil companies to leave much of their platforms’ underwater structure in place when they decommission their rigs, if they can prove doing so would offer a “net environmental benefit” to sea life. Hertzberg says that reworking the law to streamline the approval process and let oil companies keep more of the cost savings from leaving parts of the rigs in place would encourage operators to shut down platforms rather than sell them. “As much as you want to stop [drilling offshore], there’s still the rights of the people with oil and the lawsuits and all the heartache,” says Hertzberg. “Rigs-to-reefs creates an incentive model to get them to want to do it.”

But environmental advocates are dubious about claims that leaving massive underwater structures in place could benefit the ocean; some say it may increase the risk of future leaks. “It’s just another example of the oil industry externalizing their costs, and dumping all of this waste into the ocean and just leaving it out there,” says Kristen Monsell, oceans program litigation director at the Center for Biological Diversity.

Indeed, much of the regulatory architecture surrounding the U.S. oil sector was originally designed not to limit fossil fuel extraction, but to maximize it. That meant granting substantial legal rights to oil companies, and those rights are now difficult to claw back. That’s why the state of California is now paying contractors $250,000 a week to vent poison gas from an abandoned oil rig off Santa Barbara, and why it’s so hard to get rid of old, unpopular oil infrastructure, like the pipeline that spewed crude oil over some of the country’s most prized coastlines last week.

“It brought wealth and jobs and taxes and economic growth—no one cared really about shutting all this stuff down,” Rogers says. “That was a problem for future generations.”