If New York is a city of reinvention, it’s also a place of perpetual wistfulness, of missing people and things that are gone. Every day, even in the best of times, something you love about New York disappears: Your favorite restaurant can’t hack it; the awesome little card store had to close because people stopped sending cards.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

With life comes attrition. The guy who used to fix your shoes just got old and, one day, he died—there was no one to take over his business. Those of us who live here now, as the city tries to shimmer back to life amid the seemingly endless COVID crisis, feel that toothache of the heart every time we pass one of our many shuttered storefronts. Yet those of us who lived here on 9/11, and continue to live here today, have an advantage: we once saw in our city a smoking hole that also served as a mass grave for lives, and flesh, that had been incinerated in a flash on a gorgeous late-summer day.

Once you’ve seen what your city can do in the wake of that, you understand it as a place of awe as well as sorrow. Against all odds, it always comes back.

It’s true that in addition to boarded-up businesses, we have many ugly things in New York: terrible needle high-rises that splinter our already rather kooky patchwork of a skyline; streets mottled with piles of stinky garbage; a much-relied-upon subway system that’s also perpetually on the verge of falling apart. These are things that say to outsiders, “Don’t come here, to live or to play.” But they’re also an unintentionally misleading language, because all of them, even the ugly new buildings, are signs of the city’s life, evidence of its growth and change. Its workaday elements—streets and sidewalks as well as subways and buses—get used, and used hard, by its citizens.

We rely on those things, and we rely on one another too, essential truths that we learned after 9/11 even if, in our perpetual coolness—we’re Noo Yawkers, after all—we pretend to have forgotten. It’s hard to explain to anyone who wasn’t here, but the time after 9/11 was a season of undercover tenderness among New Yorkers. You might not come out and ask the stranger next to you, “Are you O.K.?” but you didn’t have to—just catching another person’s gaze could be enough.

Yet in the early days of the pandemic—as our hospitals began filling rapidly and our death toll climbed—many New Yorkers seemed unsure how we’d get through, or if we would. Whatever we’d learned from 9/11 seemed lost, or at least obscured. Many people left, for good—this New York, with no Broadway or museums or restaurants, wasn’t the New York they knew or wanted to know.

But those of us who stayed stuck around expressly to preserve the New York we knew. This city is haughty and knows its self-worth; it won’t miss its traitors. Plus, we don’t need their lousy energy. We get enough of that from outsiders who aggressively fail to understand this city, even if they professed sympathy for us after 9/11. I’m often surprised by people’s hostility toward New York and New Yorkers. In early April, when we were by far the darkest dot on the country’s COVID map, people I love—or used to love—who do not live here said things like, “Well, that’s New York.” As if, somehow, just by living so close together—a together-apartness that drives us crazy, makes us lonely and is what we live for, all in equal measure—we were asking for death.

What’s most astonishing, though, is how much New Yorkers have invested in helping one another survive. When, amid rapidly shifting public guidance, citizens worldwide were told that wearing masks could prevent the spread of the disease, New Yorkers got on board, fast. Sure, there was some early resistance, and even now you see a few scofflaws on the subway. But in such a huge and diverse city, the level of compliance is both astounding and heartening. Our motivations may not be purely altruistic—many may have their children or at-risk loved ones in mind. Still, New Yorkers inherently understand that a rising tide lifts all boats. And in that way, we hold one another above water.

Even if the threat of the pandemic never disappears completely, it will subside. New Yorkers will come through this too. Those who left, good riddance! And those outsiders who feel the city beckoning, who are ready to accept both its challenges and its pleasures—please come. You’ll be welcomed by us lifers and longtimers. New Yorkers who were babies at the time of 9/11 are now grown up, nearly ready to start their adult lives. People who were 20 at the time may be raising children of their own. And those who were middle-aged in 2001 are now thinking about what it will be like to grow old here, a bittersweet mission in a place that changes by the day, if not by the hour. The city doesn’t slow down, even when we do.

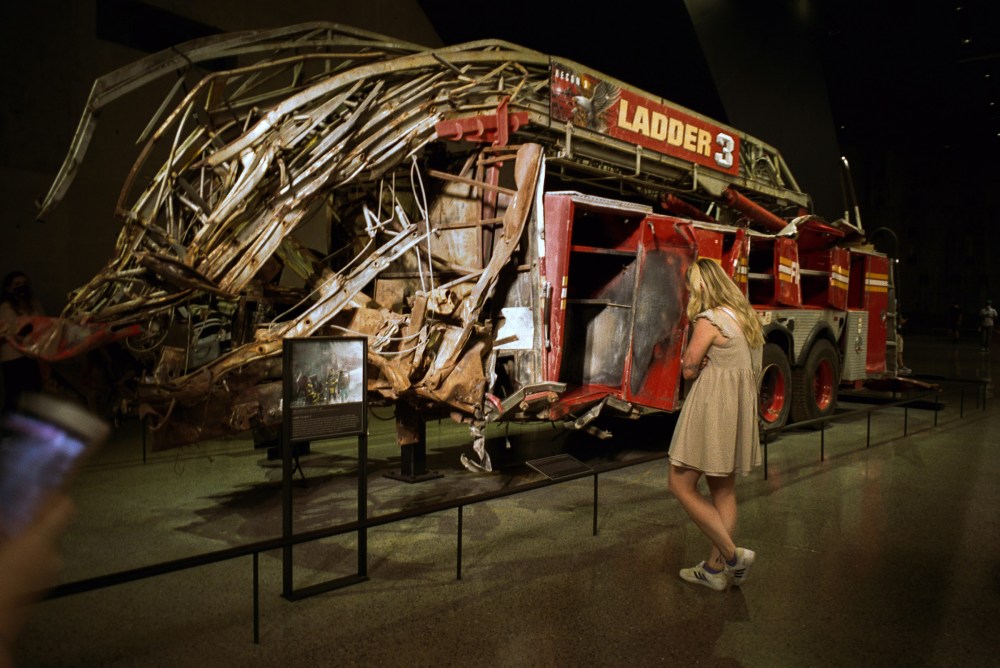

But we do have space for memories. A closed restaurant or store or nightclub is never fully forgotten, as long as there is a New Yorker alive who once loved it. We also have our own physical memorial to those who died on 9/11, which, like the buildings that once stood there, divides New Yorkers sharply. Some grumble that it’s a tourist attraction, but it’s one of my favorite spots in the city. On a hot day, the air around those deep, sloping pools is always at least 10°F cooler. It’s a place of true tranquility, of mournful reckoning, an instance of urban planning striking just the right note in the face of a city’s overwhelming grief. But as beautiful as it is, I think the truest 9/11 memorial isn’t made of granite and water. It’s the population of New Yorkers who got one another through that sooty, uncertain time of despair and signed on for anything and everything that might lie ahead. We barely speak to one another, but when we link arms, watch out. The memorial is everyone who stayed.

Daniel Arnold has been documenting life New York City since Sept. 11, 2001. You can see more of his work here.