Jeremy Cady and I first met on the plush green grass in front of the Missouri Capitol. It was the spring of 2009, and once a week or so a group of capitol staffers, reporters, and even the occasional elected official would kick a soccer ball around on a rectangular section of lawn that more often than not went unused. We’d play three-on-three, or four-on-four, depending on how many would show up. Cady and I generally guarded each other because we were both big, slow, and, well, generally lacking in superior soccer skill.

I was a capital correspondent for the state’s largest newspaper, The Post-Dispatch; Cady was a Republican staff member in the house—though he would eventually leave state government and go to work for Americans for Prosperity, a libertarian political organization funded by the Koch Brothers.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

And some nine years removed from those capitol lawn soccer games, Cady emailed me and asked if I’d be interested in speaking about the debtors’ prison columns I was writing for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch at an Americans for Prosperity event in St. Charles County. (Until that point in my career, any of my writing on the Koch Brothers or Americans for Prosperity was hardly positive—to say the least, we were strange bedfellows.) Many Republicans in Missouri had a catchy but derisive name for my employer: The Post-Disgrace, a clever shorthand to patronize the paper as too liberal. But as I wrote about rural Missourians who were caught in the never-ending cycle of abuse that criminalized poverty fosters, I often received letters that began with some version of this: “I normally disagree with your columns, but…” They were invariably from readers on the right side of the aisle.

Amid the most divided political landscape of my life, I had stumbled upon a unifying issue.

Around the same time I was invited to speak to the AFP group, Missouri’s Republican governor Mike Parson had proposed closing a state prison. It was a move contemplated by several governors in the past as Missouri struggled to deal with its ever-increasing corrections budget. Its state prison system, at the time, had a population of more than 32,000 inmates.

Several years earlier, in 2010, former representative Matt Bartle had unsuccessfully made the same proposal. It was after the Great Recession, and Missouri, like most states, had seen its revenues plummet. By 2010, without federal aid to come from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, Missouri faced a $1 billion shortfall.

Read more: The True History of America’s Private Prison Industry

Missouri’s incarceration rate of 859 people per 100,000 of total population had been steadily climbing since the late 1970s, making it the tenth highest such rate in the nation. Its corrections budget had shown a similar rise: Between 2001 and 2008, for instance, the corrections budget rose 65 percent, eating up an increasing percentage of the state’s budget.

Bartle, a thin, bespectacled attorney, is a conservative in the William F. Buckley mode, which is to say he’s intellectual about his limited-government beliefs. He came to a simple conclusion: Missouri was putting too many people in jail. There was no way to fix the state’s budget problems without closing a prison.

“One thing was clear—we were all agreed it was time to rethink criminal justice and incarceration,” Bartle told me of a consensus that was then seemingly apparent in the state’s legislature. “Both the right and the left thought so.”

“We did not do a very good job of moving the best ideas out of the room into law,” Bartle remembers—despite the leadership and support of a bipartisan group of lawmakers and judges, including key members of the majority Republican Party, there would be no prison closed that year. “But it was a reminder to me that people can get excited and innovative.”

In the decade to follow, the state’s corrections budget continued to climb. The jail and prison populations went up, not down. Missouri was hardly alone in this phenomenon, as prison populations soared across the country. Altogether, the U.S. remains the country with the highest known rate of incarceration in the world. And like Bartle, lawmakers in various states and the federal government, post–Great Recession, realized that they couldn’t keep allowing corrections budgets to increase unchecked year after year.

More than any other place in Missouri, St. Charles County straddles the rural-urban divide that so often defines political disputes in the state. This is a county where gun ownership is high and taxes are low. More than 60 percent of its voters cast a ballot for Trump in 2016. But when it comes to the debtors’ prison issue that I was at the Americans For Prosperity group to talk about, however, St. Charles County bucks conservative orthodoxy.

If you spend time in the county jail there, you might receive a board bill for your time behind bars, like nearly every other rural county in Missouri. But unlike most, St. Charles County takes a person’s ability to pay into consideration.

“Our general rule of thumb is if the person is indigent—which is about 80 percent of our defendants—we don’t try to collect,” says St. Charles County prosecuting attorney Tim Lohmar, a Republican. (That number of poor defendants—80 percent—is not unusual. Various studies have shown that is the percentage of people charged with crimes in the U.S. that qualify for a public defender, a fair definition of living in some stage of poverty.)

But few counties in Missouri take ability to pay into account when charging board bills or other court costs or fees. That should offend the sensibilities of conservatives, Republican state representative Tony Lovasco told me at the Americans For Prosperity event. Lovasco is a member of the state’s House Special Committee on Criminal Justice. That committee would later hear, and pass, a bill that made it illegal to put people in jail who couldn’t afford to pay for court fines and fees, including board bills.

Here’s the truth about Lovasco and his fellow conservatives that night: They got it. They understood and cared about the injustice of their fellow Missourians being jailed again simply because they couldn’t afford the bill they received for previous time spent in jail. Some folks saw a form of double jeopardy, people being punished twice for the same, minor crimes. Others recognized it as a backdoor tax.

They helped answer a question that had been bugging me ever since I started writing a series of columns on American debtors’ prisons. Why was it that conservatives were joining liberals in advocating for criminal justice reform, particularly related to how the judicial system was being used to criminalize poverty?

If the courts are used as a debt-collection service, and that drives law enforcement decisions, then it bastardizes the entire purpose of the judicial branch of government and puts public safety at risk, explains Marc Levin, chief policy counsel at the Council on Criminal Justice and a senior advisor to the Right on Crime initiative (which he helped develop at the Texas Public Policy Foundation). He speaks in a language understood by conservatives about the tyranny of government and the deprivation of liberty by courts that don’t take into consideration the civil rights protections for the people who come before judges but can’t afford to pay the costs heaped upon them.

“I think it is important to both utilize coalitions across ideological lines… but also continue to have both conservative and liberal groups each speak to their own constituencies, both within the public and among policymakers,” Levin says.

If America wants to ever win the so-called War on Poverty, then the criminal justice system must be the front lines, with an ever-increasing focus by those in charge of it to protect the civil rights of the people too often abused by a system more focused on tax collection than keeping local communities safe. Every judge, every prosecutor, every public defender in the country must ask themselves before they make a decision in the sorts of misdemeanor and traffic cases they rush through every day on crowded dockets: Can this person afford to pay the fines and fees the statutes call for in this case? Will jailing this person make my community safer? What must be done to make sure every defendant in this courtroom has their civil rights defended in the same way, regardless of if they have money, or don’t?

There are solutions currently making their way through both the courts and state capitols—all with some form of bipartisan support: Getting rid of cash bail, and ending the practice of putting people back in jail if they can’t afford a bill for their previous stay. (Better yet, don’t charge poor people for their time behind bars at all.)

States should also stop using court fines and fees as a primary revenue source for local governments, and limit the amount of revenue cities and counties can collect from driving tickets or court fines and fees. Taking this concept a step further, Pennsylvania Treasurer Joe Torsella in early 2021 wrote the nation’s credit-rating agencies and asked them to take into consideration a city’s reliance on fines and fees for revenue when considering municipal bond ratings.

None of these ideas are radical, and each have been adopted or supported in some capacity by lawmakers in both Democratic-and Republican-leaning states. But to fully implement them, they must go national, and lawmakers are going to have to deal with the consequences of not relying on the revenue sources they have depended upon to the detriment of their constituents who live in a state of poverty.

There can be no sale of justice in a free America. Until the country elevates that value, Lady Justice isn’t blind, and her scales are completely out of balance.

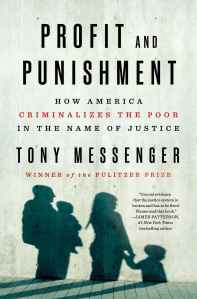

Adapted from Profit and Punishment: How America Criminalizes the Poor in the Name of Justice by Tony Messenger. Copyright © 2021. Available from St. Martin’s Press.