There are dozens of routes that Alaska Airlines Flight 1405 can take from Oklahoma City to Seattle, and dispatcher Brad Ward zeroed in on what he thought was the best one, taking into account weather, wind speeds, and other air traffic.

But his new colleague at the Alaska Airlines operations center had other thoughts.

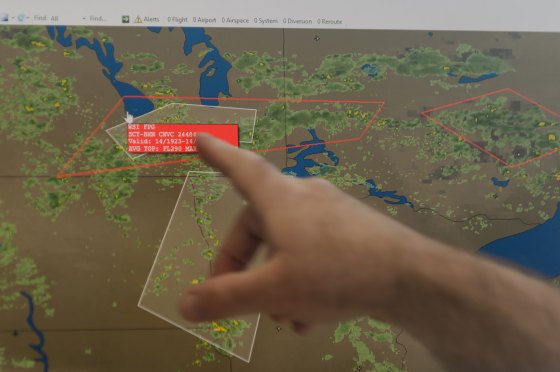

A storm cell near Oklahoma City was likely to turn into a thunderstorm around the time Flight 1405 took off, and the airspace north of Amarillo would be closed for military exercises. Better to reroute, the young colleague said, suggesting an alternative that Ward admitted was safer and more efficient. The entire conversation lasted just seconds and passed without a word being spoken: a red box lit up on Ward’s computer screen when the colleague, an artificial intelligence program he has affectionately nicknamed Algo, had an idea.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

“This is the smartest person in the room,” says Ward, a solidly built man with the corner desk who has been a flight dispatcher for 21 years, responsible for planning flight routes and submitting them to air traffic control for approval. He gestures to the program running silently on his computer. “It’s smarter than me.”

Read more: Airlines’ Emissions Halved During the Pandemic. Can the Industry Preserve Some of Those Gains?

Algo’s formal name is Flyways, and it’s the product of a Silicon Valley company called Airspace Intelligence, which is hoping to make air travel more efficient and safer as airlines try to recover from a year in which the pandemic ravaged the travel industry. The idea of AI setting paths for jets streaking through the skies at hundreds of miles per hour might sound terrifying, but Flyways does not dictate—it advises, and humans always have the final say.

This is a job Ward used to do alone by flipping through tabs on his computer screen and guessing where a flight would be when it encountered rough weather or other conditions. Now he has Algo, who dispenses advice, never gets tired, doesn’t get sick and is always in the office. Its machine learning enables Flyways to spot weather threats and other potential problems before humans are aware of them, which helps dispatchers and pilots avoid stressful last-minute changes. Once, when a government website showing restricted airspace went offline, Algo remembered which areas were usually closed to commercial flights at certain times and planned routes accordingly.

For all the fears that artificial intelligence will replace our jobs, the more common application of AI in the workplace today is as a colleague, like Algo is to Ward. It can search CT scans for early signs of lung cancer, alerting radiologists to lesions they may have overlooked. It can come up with millions of possible designs for a chair working within parameters provided by designers. It can analyze an applicant’s body language and voice tone in interviews, speeding up the hiring process. A growing number of workers are interacting with multiple forms of AI as they go about their jobs every day.

<strong>“The sky is really the big untapped opportunity.”</strong>“A man/machine collaboration will do better than just a man or just a machine,” says Pedro Domingos, a professor of computer science at the University of Washington. Deep Blue, an IBM program, may have beaten Gary Kasparov at chess, he says, but “centaur chess teams,” in which humans worked with AI, beat both humans and machines. “It’s not that people will be out of jobs, it’s that they will use computers to do their jobs more,” Domingos says.

Of course, as workers become more productive, companies may need fewer of them doing the same job. Transport aircraft used to have as many as five people in the cockpit in the 1940s; now commercial planes have two. Some workers will have to learn new skills as their jobs change. Companies closed call centers during the pandemic and deployed AI chatbots, for example, in many cases leaving customer service agents to deal with complicated questions that the chatbots couldn’t answer; they were also needed to train and supervise the chatbots.

Phillip Buckendorf, the 30-year-old CEO and co-founder of Airspace Intelligence, came up with the idea for Flyways after visiting a flight dispatch center. Like most people, he figured it would look something like Star Trek, with complicated computer systems helping dispatchers guide planes through the skies. Buckendorf instead found that many dispatch centers looked like accounting firms from the 1990s. Dispatchers often relied on paper printouts to see weather forecasts and figured out wind speeds by decoding strings of letters and numbers on a federal website.

Buckendorf, a lanky German who had been working for a self-driving car company, liked the idea of applying to planes in flight the same kind of technology that teaches cars to avoid traffic jams or double-parked vehicles. “You have this incredibly dynamic environment where you want to predict— where are you going to be in the airspace? And what does the environment look like? And how do you optimize for that?” says Buckendorf, who camped out at the Alaska Airlines dispatch center in Seattle for months alongside his co-founders, collaborating with dispatchers like Brad Ward to build Flyways.

He approached various airlines with his idea but says Alaska was the quickest to agree to a trial, and in May 2020 it began using Flyways on all of its continental flights for a six-month trial. During that time, the AI found an opportunity to reduce flight times and fuel on 64% of the flights, says Pasha Saleh, Alaska Airlines’ director of strategy and innovation. It cut an average of 5.3 minutes off each Alaska Airlines flight, saving a total of 480,000 gallons of fuel and avoiding 4,600 tons of carbon emissions. (Aircraft fuel consumption varies and has improved over the years, but large jetliners can burn anywhere from 600 to 750 gallons of fuel an hour. According to one study, a person flying on a round-trip trans-Atlantic flight accounted for about 1.6 tons of carbon emissions.)

The airline, which gave TIME an exclusive look at how the system operates from the dispatchers’ and pilots’ point of view, is now rolling out Flyways to all of its flights, including the ones that go to Alaska and Hawaii, and while it would not say how much it pays for the program, the reduced flight times and fuel consumption seen in the trial could translate to millions of dollars in savings in the long run.

In terms of places to improve efficiency, “the sky is really the big untapped opportunity,” says Saleh.

<strong>“This is just a huge enhancement to what we do.”</strong>On a recent Friday, Alaska Airlines Captain Kat Pullis scrolled through an iPad outside Gate D4 at the Seattle-Tacoma International Airport, reviewing the route for Flight 1258 to San Francisco. Pullis, who was wearing small airplane stud earrings, wanted to be sure the Airbus 321 she was piloting wasn’t going to encounter bad weather. Flyways, working in tandem with Ward, had found the most efficient route, which would take Pullis west of the Puget Sound, past waypoints ETCHY and PYE near Point Reyes, and into San Francisco from the west.

Pullis climbed into the cockpit, a silver shell of panels, switches and levers, and uploaded the route into the plane’s system, using an iPad in a rose-colored case. It’s a far cry from just 10 years ago, when pilots like Pullis dragged around 35-pound suitcases filled with paper flight manuals. Ward texted her a greeting, using the ever-evolving technology that would enable him to stay in touch with Pullis throughout the trip and offer assistance if needed.

“This is just a huge enhancement to what we do,” says Ward, whose desk looks out onto a parking garage, a Silver Dollar casino, and the Seattle airport a mile away, where Pullis was preparing for flight.

Not every human/AI relationship is as harmonious as Ward’s and Algo’s, either. A warehouse worker who is told where to walk and what packages to pick by an AI algorithm may find that AI makes the job more physically grueling and stressful. And assuming that AI will be a good colleague has repercussions. Experts said as early as 2017 that AI could diagnose pneumonia better than a radiologist could, which led to a shortage of radiologists being trained, says Gary Marcus, a NYU professor who co-wrote the book Rebooting AI: Building Artificial Intelligence We Can Trust.

Yet that AI software is still years from being deployed on a large scale. Companies that use AI to screen loan or mortgage applications often incorporate bias, making it more expensive for Black and Latino families to get loans. Police departments that use AI for facial recognition have wrongfully arrested Black men when the software mistakenly identified them as suspects. Because humans design AI, they can feed their own biases into the algorithms, such as when an AI recruiting tool designed by Amazon discriminated against female applicants.

But AI is here to stay, and an AI colleague or colleagues can be an advantage as pandemic-era cutbacks force employees to take on extra tasks, all the while dealing with the distractions—think Slack, emails, instant messaging and video meetings—of the modern workplace. AI transcribed the interviews I did for this story, replied to emails scheduling those interviews, and alerted me to spelling errors in my draft.

In the transportation industry in particular, automation and AI could help address impending labor shortages; as people venture out of lockdown and air traffic picks up, experts predict a pilot shortage. The trucking industry is already experiencing driver shortages. That’s before drones and unmanned aircraft make the airspace even more crowded, necessitating more dispatchers and air traffic controllers.

<strong>“There’s no way humans can grasp how to handle 20 or 30 airplanes going into one place at one time.”</strong>Each time you board a commercial flight in the U.S., there is a flight dispatcher somewhere who has plotted your route. Commercial airplanes must pass over a number of “waypoints”—essentially geographic coordinates with names like IKPIF or KUJEF—as they go from Point A to Point B. The dispatcher chooses which waypoints a flight should hit, then submits the plan to air traffic controllers at the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), who either approve or deny the route.

The algorithm from Flyways draws on data from past flights and current and predicted conditions to run through millions of route possibilities, and it reruns the process every few minutes for every flight. A red box lights up on the dispatcher’s screen if Flyways suggests a flight should be rerouted because of weather or safety issues; a green box lights up if a re-route is suggested for fuel efficiency; purple means a flight needs to be routed around restricted airspace.

The predictive nature of Flyways can help dispatchers avoid things that they can’t see. If it knows that a storm cell in a geographic area usually grows or moves in a certain direction, it can find a new path before that storm shows up on weather maps. If many pilots have reported turbulence on their flights, it can map that turbulence and route other flights to avoid it.

If it knows that many flights are planning to approach Seattle from the north later in the day, it may suggest approaching the airport from the south to avoid congestion. “There’s no way humans can grasp how to handle 20 or 30 airplanes going into a place at one time,” says Ward, who stands, in khakis and a green polo shirt, in front of the four monitors he uses to do his job. “You can have everyone on what you think is an optimal route, but then you create a traffic jam.”

Flyways also shows Ward flights that can be slowed down for “network efficiency,” indicating how making one flight arrive later could help four other flights land earlier.

Sometimes, Flyways suggests routes that Ward would never have tried. That’s when his judgement comes in handy. The FAA prefers that most flights from the east coast to the northwest go over Cleveland, for example, because this avoids traffic jams. If Flyways suggests a different route, Ward will often reject it because he knows that the FAA won’t accept it. If Flyways decides a flight can go close to a storm because there’s a strong chance the storm will dissipate, Ward may reject that route as too risky.

Dispatchers accepted 32% of Flyways recommendations during the Alaska Airlines trial period, but that is expected to increase as Flyways memorizes dispatchers’ choices. Algo is already learning to plot more routes over Cleveland.

“Humans will always be better at making the decisions. And the computer will always be better at supporting those decisions with good information.” says Ward, a self-described nerd who used to spend countless hours trying to find the best routes for his flights.

Read more: Artificial Intelligence Could Help Solve America’s Impending Mental Health Crisis

Alaska hopes to eventually use Flyways to figure out which flights have a lot of passengers making connections when they land, and to slow down other flights so that the connecting passengers can land on time. It could eventually tell Ward which planes have passengers transferring from one flight to another, so he can put them at adjoining gates. Alaska has 67 full-time dispatchers, and all are now trained to use Flyways.

Airspace Intelligence says it is actively working with “multiple U.S. airlines” to deploy Flyways in their operations centers. Over time, if AI helps Ward make customers’ flight experiences more pleasant and less expensive, more people will fly, Domingos says, creating the need for more dispatchers.

That’s what happened in the banking industry initially when ATMs were introduced. More people started using banks, so more branches were opened. The number of tellers increased, and their jobs evolved as they spent less time doling out cash and more time offering financial advice to customers. Now, the number of bank tellers is falling, but the number of financial advisors is projected to grow over the next decade.

AI has long been creeping into airspace. So many parts of piloting an airplane are done by computers that some pilots spend as little as three minutes actually “flying” the plane, says Mary “Missy” Cummings, a Duke professor who directs the Humans and Autonomy Lab at Duke Robotics and who was one of the Navy’s first female fighter pilots. Manufacturers are talking about designing passenger planes for only one pilot.

As companies add drones and autonomous vehicles to the airspace, artificial intelligence will become more essential, Cummings says. There are already “near-misses” at airports because of heavy traffic, and that’s before drones begin flying at different speeds and levels, she says. “We’ll never be able to integrate unmanned vehicles without automation,” she says.

That doesn’t mean humans won’t be needed, though—in aviation, there are always times when something unexpected like a thunderstorm or a flock of geese requires a human reaction. Besides, passengers want to know there is a human involved who will share their fate if something happens to the plane, says Cummings. There’s a reason it is comforting to walk by the cockpit when you board a plane.

As Captain Pullis prepared to take off for San Francisco, she came on the plane’s loudspeaker, introducing herself and telling the passengers that their flight would be an hour and 33 minutes and they’d be cruising at 33,000 feet.

She reminded them to keep their masks on and then added something very human. “I just want to let you know — I am so happy to see all your beautiful, wonderful eyes—it’s been a rough year,” Pullis said.

There was nothing artificial about it. A few passengers nodded in understanding.