- The youngest exoplanet yet discovered is less than 1 million years old and orbits Coku Tau 4, a star 420 light-years away. Astronomers inferred the planet’s presence from an enormous hole in the dusty disk that girdles the star. The hole is 10 times the size of Earth’s orbit around the Sun and probably caused by the planet clearing a space in the dust as it orbits the star.

- Exoplanets are planets beyond our own solar system. Thousands have been discovered in the past two decades, mostly with NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope.

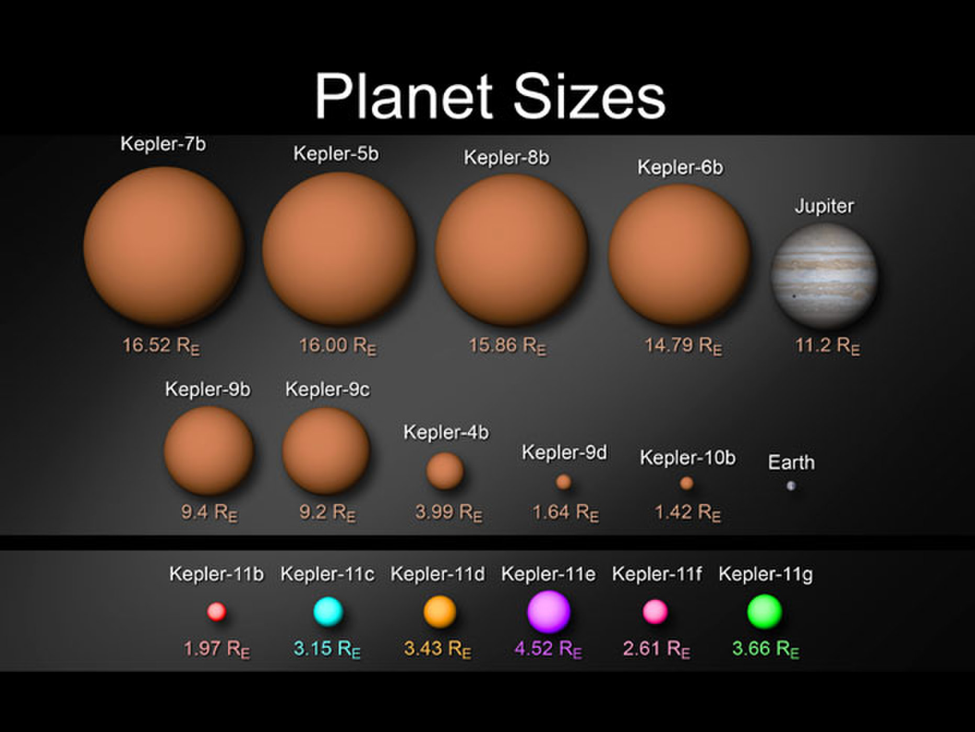

- These worlds come in a huge variety of sizes and orbits. Some are gigantic planets hugging close to their parent stars; others are icy, some rocky. NASA and other agencies are looking for a special kind of planet: one that’s the same size as Earth, orbiting a sun-like star in the habitable zone.

- The habitable zone is the range of distances from a star where a planet’s temperature allows liquid water oceans, critical for life on Earth. The earliest definition of the zone was based on simple thermal equilibrium, but current calculations of the habitable zone include many other factors, including the greenhouse effect of a planet’s atmosphere. This makes the boundaries of a habitable zone “fuzzy.”

- Astronomers announced in August 2016 that they might have found such a planet orbiting Proxima Centauri. The newfound world, known as Proxima b, is about 1.3 times more massive than Earth, which suggests that the exoplanet is a rocky world, researchers said. The planet is also in the star’s habitable zone, just 4.7 million miles (7.5 million kilometers) from its host star. It completes one orbit every 11.2 Earth-days. As a result, it’s likely that the exoplanet is tidally locked, meaning it always shows the same face to its host star, just as the moon shows only one face (the near side) to Earth.

- Most exoplanets have been discovered by the Kepler Space Telescope, an observatory that began work in 2009 and is expected to finish its mission in 2018, once it runs out of fuel. As of mid-March 2018, Kepler has discovered 2,342 confirmed exoplanets and revealed the existence of perhaps 2,245 others. The total number of planets discovered by all observatories is 3,706.

Early discoveries

- While exoplanets were not confirmed until the 1990s, for years beforehand astronomers were convinced they were out there. That wasn’t just wishful thinking, but because of how slowly our own sun and other stars like it spin, University of British Columbia astrophysicist Jaymie Matthews told Space.com. Matthews, the mission scientist of occasional exoplanet telescope observer MOST (Microvariability and Oscillations of STars), was involved in some of the early exoplanet discoveries.

- Astronomers had an origin story for our solar system. Simply put, a spinning cloud of gas and dust (called the protosolar nebula) collapsed under its own gravity and formed the sun and planets. As the cloud collapsed, conservation of angular momentum meant the soon-to-be-sun should have spun faster and faster. But, while the sun contains 99.8 percent of the solar system’s mass, the planets have 96 percent of the angular momentum. Astronomers asked themselves why the sun rotates so slowly.

- The young sun would have had a very strong magnetic field, whose lines of force reached out into the disk of swirling gas from which the planets would form. These field lines connected with the charged particles in the gas, and acted like anchors, slowing down the spin of the forming sun and spinning up the gas that would eventually turn into the planets. Most stars like the sun rotate slowly, so astronomers inferred that the same “magnetic braking” occurred for them, meaning that planet formation must have occurred for them. The implication: Planets must be common around sun-like stars.

- For this reason and others, astronomers at first restricted their search for exoplanets to stars similar to the sun, but the first two discoveries were around a pulsar (rapidly spinning corpse of a star that died as a supernova) called PSR 1257+12, in 1992. The first confirmed discovery of a world orbiting a sun-like star, in 1995, was 51 Pegasi b — a Jupiter-mass planet 20 times closer to its sun than we are to ours. That was a surprise. But another oddity popped up seven years earlier that hinted at the wealth of exoplanets to come.

- A Canadian team discovered a Jupiter-size planet around Gamma Cephei in 1988, but because its orbit was much smaller than Jupiter’s, the scientists did not claim a definitive planet detection. “We weren’t expecting planets like that. It was different enough from a planet in our own solar system that they were cautious,” Matthews said.

- Most of the first exoplanet discoveries were huge Jupiter-size (or larger) gas giants orbiting close to their parent stars. That’s because astronomers were relying on the radial velocity technique, which measures how much a star “wobbles” when a planet or planets orbit it. These large planets close in produce a correspondingly big effect on their parent star, causing an easier-to-detect wobble.

- Before the era of exoplanet discoveries, instruments could only measure stellar motions down to a kilometer per second, too imprecise to detect a wobble due to a planet. Now, some instruments can measure velocities as low as a centimeter per second, according to Matthews. “Partly due to better instrumentation, but also because astronomers are now more experienced in teasing subtle signals out of the data.”

Kepler, TESS and other observatories

- Kepler launched in 2009 on a prime mission to observe a region in the Cygnus constellation. Kepler performed that mission for four years — double its initial mission lifetime — until most of its reaction wheels (pointing devices) failed. NASA then put Kepler on a new mission called K2, in which Kepler uses the pressure of the solar wind to maintain position in space. The observatory periodically switches its field of view to avoid the sun’s glare. Kepler’s pace of planetary discovery slowed after switching to K2, but it is still found hundreds of exoplanets using the new method. Its latest data release, in February 2018, contained 95 new planets.

- Kepler has revealed a cornucopia of different types of planets. Besides gas giants and terrestrial planets, it has helped define a whole new class known as “super-Earths”: planets that are between the size of Earth and Neptune. Some of these are in the habitable zones of their stars, but astrobiologists are going back to the drawing board to consider how life might develop on such worlds. Kepler’s observations showed that super-Earths are abundant in our universe. (Oddly, our solar system doesn’t appear to contain a planet of that size, although some believe a large planet nicknamed “Planet Nine” may be lurking in the outer reaches of the solar system.)

- Kepler’s primary method of searching for planets is the “transit” method. Kepler monitors a star’s light. If the light dims at regular and predictable intervals, that suggests a planet is passing across the face of the star. In 2014, Kepler astronomers (including Matthews’ former student Jason Rowe) unveiled a new “verification by multiplicity” method that increased the rate at which astronomers promote candidate planets to confirmed planets. The technique is based on orbital stability — many transits of a star occurring with short periods can only be due to planets in small orbits, since multiply eclipsing stars that might mimic would gravitationally eject each other from the system in just a few million years.

- As Kepler wraps up its mission, a new observatory called the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) is expected to launch in spring 2018. TESS will orbit the Earth every 13.7 days and will perform an all-sky survey over two years. It will survey the Southern Hemisphere in its first year, and the Northern Hemisphere (which includes the original Kepler field) in its second. The observatory is expected to reveal many more exoplanets, including at least 50 that are around the size of Earth.

Other prominent planet-hunting observatories (past and present) include:

- The HARPS spectograph on the European Southern Observatory’s La Silla 3.6-meter telescope in Chile, whose first light was in 2003. The instrument is designed to look at the wobbles that a planet induces in a star’s rotation. HARPS has found well over 100 exoplanets itself, and is regularly used to confirm observations from Kepler and other observatories.

- The Canadian Microvariability and Oscillations of STars (MOST) telescope, which started observations in 2003. MOST is designed to observe a star’s astroseismology, or starquakes. But it also has participated in exoplanet discoveries, such as finding the exoplanet 55 Cancri e.

- The French Space Agency’s CoRoT (COnvection ROtation and planetary Transits), which operated between 2006 and 2012. It found a few dozen confirmed planets, including COROT-7b — the first exoplanet that had a predominantly rock or metal composition.

- The NASA/European Space Agency Hubble and NASA Spitzer space telescopes, which periodically observe planets in visible or infrared wavelengths, respectively. (More information about a planet’s atmosphere is available in infrared.)

- The European CHaracterising ExOPlanets Satellite (CHEOPS), which is expected to be ready for launch in 2018. The mission is designed to calculate the diameters of planets accurately, particularly those planets that fall between super-Earth and Neptune masses.

- The NASA James Webb Space Telescope, which is expected to launch in 2020. It is specialized to observe in infrared wavelengths. The powerful observatory is expected to reveal more about the habitability of certain exoplanets’ atmospheres.

- The European Space Agency’s PLAnetary Transits and Oscillations of stars (PLATO) telescope, which is expected to launch in 2024. It is designed to learn how planets form and which conditions, if any, could be favorable for life.

- The ESA ARIEL (Atmospheric Remote-sensing Infrared Exoplanet Large-survey) mission, which will launch in mid-2028. It is expected to observe 1,000 exoplanets and also do a survey of the chemical compositions of their atmospheres.

Notable exoplanets

With thousands to choose from, it’s hard to narrow down a few. Small solid planets in the habitable zone are automatically standouts, but Matthews singled out five other exoplanets that have expanded our perspective on how planets form and evolve:

- 51 Pegasi b: As mentioned earlier, this was the first planet to be confirmed around a sun-like star. Half the mass of Jupiter, it orbits around its sun at roughly the distance of Mercury from our Sun. 51 Pegasi b is so close to its parent star that it is likely tidally locked, meaning one side always faces the star.

- HD 209458 b: This was the first planet found (in 1999) to transit its star (although it was discovered by the Doppler wobble technique) and in subsequent years more discoveries piled up. It was the first planet outside the solar system for which we could determine aspects of its atmosphere, including temperature profile and the lack of clouds. (Matthews participated in some of the observations using MOST.)

- 55 Cancri e: This super-Earth orbits a star that is bright enough to see by eye, meaning astronomers can study the system in more detail than almost any other. Its “year” is only 17 hours and 41 minutes long (recognized when MOST gazed at the system for two weeks in 2011). Theorists speculate that the planet may be carbon-rich, with a diamond core.

- HD 80606 b: At the time of its discovery in 2001, it held the record as the most eccentric exoplanet ever discovered. It is possible that its odd orbit (which is similar to Halley’s Comet around the sun) may be due to the influence of another star. Its extreme orbit would make the planet’s environment extremely variable.

- WASP-33b: This planet was discovered in 2011 and has a sort of “sunscreen” layer — a stratosphere — that absorbs some of the visible and ultraviolet light from its parent star. Not only does this planet orbit its star “backward,” but it also triggers vibrations in the star, seen by the MOST satellite.

Exoplanets: Worlds Beyond Our Solar System was originally published in Exponential Technologies / Industrial Revolutions Based Infrastructure on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.